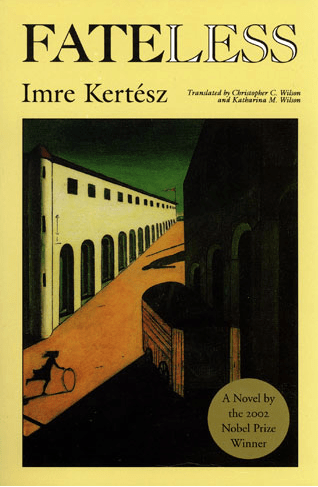

Imre Kertész novel Fateless – Sorstalanság tells the story of fifteen-year old Gyuri Köves, a Jewish boy who lives in Budapest. It starts in 1944, on the day on which Gyuri’s father is sent to a labour camp. What strikes the reader from the beginning is the narrator’s voice and his cluelessness. He’s a young boy, interested in girls and puzzled by his parents strange arrangements (he lives with his father and his stepmother and his parents often quarrel because his mother wants him to live with her). He notices everything that goes on around him but his interpretations are always slightly off. He finds logic in many shocking things, like the yellow star they have to wear, the way they are being treated by non-Jews and many other things. Why? Because they seem logical, from a certain point of view. And because he doesn’t feel like a Jew. His family isn’t religious. They even eat porc during the last dinner with his father. He feels that the star and being ostracized hasn’t really anything to do with him. It’s not personal.

A little later Gyuri is sent to work in a factory and then, one morning, has to get off the bus and wait endlessly for a train to take him and others to another “work place”. Of course, the reader knows it’s a concentration camp. He’s first sent to Auschwitz, then to Buchenwald and later to Zeitz.

He still finds logic in everything he sees. In the way they are forced to work, in the way they are punished. That doesn’t mean he doesn’t suffer. He’s cold, dirty and constantly hungry. He witnesses executions and is afraid of being sent to the gas chambers.

Towards the end of the book, he falls ill and is sent back to Buchenwald until the day the camp is freed and he can return to Budapest.

Reading a novel, set to large parts in a concentration camp, filtered through the consciousness of a narrator like this, was a peculiar and eerie experience. It could have gone wrong. It could have felt sensationalist and dishonest like The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (I’m referring to the movie not the book), but it didn’t. It’s chilling because we know what he’s talking about but he doesn’t. When Gyuri tells us how everyone stepping off the train is inspected and then either sent to one group or the other, we know that it means that they will either be sent to a labour camp or to the gas chambers. Reading Gyuri’s assessment of what happens, his feeling of being chosen and found worthy – without knowing the real logic behind it all – is almost creepy.

The best novels don’t just follow a character from the beginning to the end but they show a change. And Gyuri does change. The boy who’s leaving the concentration camp is bitter and full of hatred. The days of his admiration for a system that runs,logically, smoothly, and mercilessly are long gone.

I’ve seen this novel called “shocking” and, if you’ve read my review until now, you may think, you know why. Because of the distortion. But that’s not the shocking part. What may seem odd is the end of the book. It’s not a plot element, therefore, I don’t consider it to be a spoiler to reveal the end. When Gyuri returns to Budapest, people refer to the horrors he must have seen or ask him whether it was like hell. He tells them that he hasn’t seen hell and therefore he doesn’t know how to compare. And he finds it absurd when people tell him to start a new life, leave what has happened behind. But it’s not likely he will ever forget. What he doesn’t tell them is, that there were moments of great happiness in the concentration camp. And that’s the shocking thing of the novel. It shows us that we cannot imagine something we haven’t experienced. Whether we think, like some, it wasn’t all that bad or whether we assume it was “hell” – we have no clue. Both assumptions are equally faulty. And there’s a certain arrogance in a assuming that we can picture what we don’t know. And there can always be happiness. This reminded me of one of my favourite books – Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

The end also reveals the meaning of the title. The novel describes many instances in which the Jews let the oppressor handle them like cattle. They never fight back. This, as Gyuri says, was a choice. Everything was a choice. There’s no such thing as “fate” – everybody is ultimately free, free to choose how to act. Always.

I wish this review was more eloquent but I’ve got the flu since Monday and my head is fuzzy. I’m sorry for that. It’s a book that would have deserved a careful review because it’s stunning. I really liked it a great deal and, for once, “like” isn’t a badly chosen word, even though I’m writing about a Holocaust novel.

I have watched the movie as well and found it powerful. It stay’s close to the novel, with the exception of the last parts. In the movie Gyuri is offered to go to the US when the camp is freed by the Americans. Going back to Hungary means going to the Russian sector. Nothing to look forward to. This isn’t a topic in the book.

The book is based on Kertész’s own experience. As a fourteen-year old he was sent to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald. Interestingly he says that the book is far less autobiographical than the movie.

Other reviews

Emma (Book Around the Corner)

*******

Fateless is the third book in the Literature and War Readalong 2015. The next book is the German novel A Time to Love and a Time to Die – Zeit zu leben und Zeit zu sterben by Erich Maria Remarque. Discussion starts on Friday 27 November, 2015. Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2015, including the book blurbs can be found here.