Until not too long ago, even Germans thought it was in bad taste to write about German suffering during WWII. The feeling of guilt ran too deep. I still remember the discussion when the movie Anonyma came out in 2008. It’s based on the diary of a German woman who was in Berlin when the Russian army arrived. She was one of 2,000,000 German women who were raped many times by the Russian troops. We may look at the war any which way we want, there’s no denying that the Germans suffered too. We just have to think of the bombing of Dresden, the mass rapes of German women by Russian troops and – of course – the huge number of people who were forced to flee from the East towards the West, when the war was lost. Many of these Germans would never be able to return because the place they came from wouldn’t be part of Germany anymore.

This may seem a lengthy introduction but it’s essential to understand not only the importance but the scope of Walter Kempowskis’ powerful and chilling novel All For Nothing – Alles umsonst .

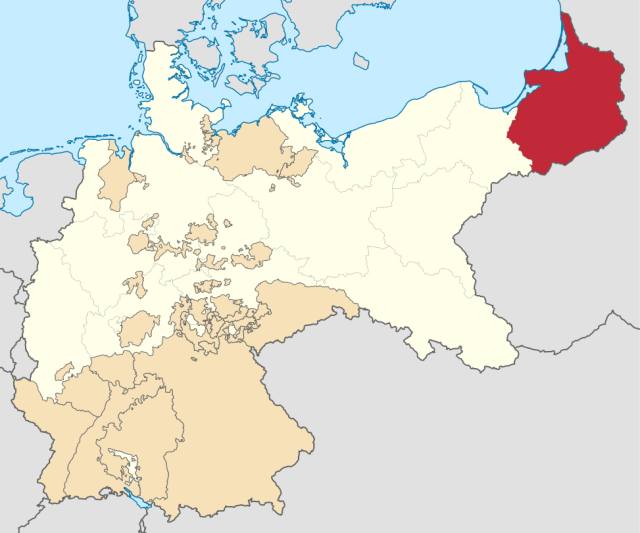

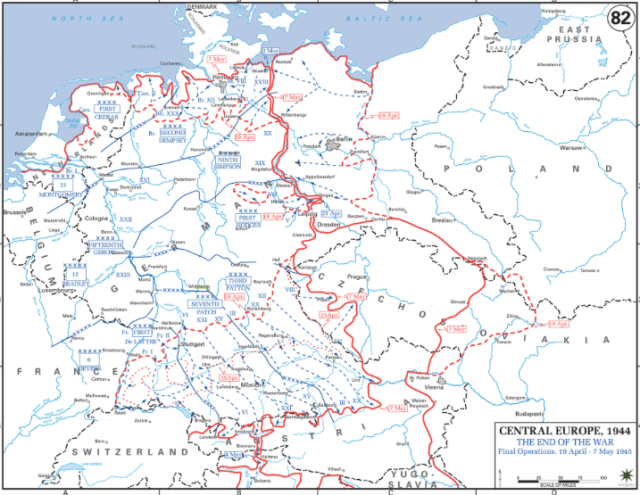

All for Nothing is set in East Prussia, in the winter of 45. In January, to be precise. The story mostly takes place on the Georgenhof estate, located near Mitkau, not too far from Königsberg. Königsberg which was once famous was almost completely destroyed and is now called Kaliningrad. For further understanding, I’ve added two maps.

The map above shows East Prussia in red. The other one below, is a map from 1945. It is more detailed and shows other territories. It’s easy to understand when you look at the maps, how precarious the situation was for the civilians in East Prussia when the Russians started to advance.

At the beginning of the novel, people already start to flee in the direction of Berlin, only the people on Georgenhof, the von Globig’s, behave as if nothing was happening. This is mostly due to Katharina von Globig’s character. She’s the wife of the estate owner who is serving in Italy. Together with her twelve-year-old son, her husband’s elderly aunt and Polish and Ukrainian servants, she lives a life of carefree ease. She’s someone who likes to withdraw from the world, into her own realm. She lives in an apartment inside of the large estate where nobody is allowed to enter. Here she reads, dreams, smokes, cuts out silhouettes, and thinks of an affair she had some years ago. Possibly the only time in her life in which she was really happy.

The aunt is a typical old maid. In the absence of her nephew, and knowing how little Katharina cares, she is in charge of the estate. Peter, the son, who should be with the Hitler Youth, pretends he’s got a cold and, like his mother, flees to other realms in his imagination.

When the first refugees arrive, the small household welcomes them. They feed and entertain them, just as if they were ordinary guests. Katharina may be distracted but she’s kind and generous. Even though her husband calls her occasionally and urges her to leave, she stays put.

But some of the refugees tell horror stories and even Katharina and the aunt realize that falling into the hands of the Russians might prove fatal. Only their life is so comfortable, so enjoyable, how can they leave everything behind? This is an incredible dilemma, and one can easily understand how so many waited far too long before they finally fled.

In the case of the von Globig’s it needs a tragedy that finally pushes them to make a decision.

The first half of the book tells the story before they flee, the second half, tells the story of the flight.

It was so strange, but reading the first almost peaceful part was really stressful. The reader knows what’s coming but the character’s don’t. It takes so long until it sinks in that all is lost.

The descriptions of the flight, those long, endless treks of refugees is harrowing. Not only are the Russians pushing forward, but the refugees are bombed and dead people and horses are piled up to the left and the right of the roads.

Kempowski did a great job at describing in a poignant way how this must have been without traumatizing the reader. We read, breathlessly, but it’s not too graphic and the characters are held at arm’s length. That doesn’t mean the book left me cold. Not at all but it never felt like it was manipulative and trying to shock and disgust.

People often say “Why didn’t they leave earlier?” when speaking of people who are trapped in a war zone. When you read this, you get a good feeling for the reasons. Not only do they have to abandon everything, but they have no idea whether it will be better where they are going. Besides, back then, all they had was accounts of a few other refugees and British radio. Their own radio told them that it was negative propaganda, that all was well, the frontline still secure. How would you have known for sure?

The luckiest thing may have been that they fled back to their own homeland and could stay on territory in which their own language was spoke. While many didn’t make it and many had a very uncertain future, they had at least that. Unlike the refugees that come to Europe from the war zones in the Middle East.

Before ending, I’d like to say a few things about the characters and Kempowski’s style. He does something I’ve never seen before. Almost every other sentence ends in a question mark. It’s really bizarre and I’m surprised it didn’t annoy me. Interestingly, it felt like we hear the characters question themselves all the time. I read a few reviews and apparently he tried to show the general confusion. I’d say he was very successful but it takes some getting used to. His characters are very well drawn. Even minor characters come to life. Most of the time he uses indirect speech but you can still hear the different mannerisms. People repeat the same stories again and again. Just like in real life. Sometimes that’s quite funny. People can be so absurd. Petty. Self-absorbed. Ridiculous. Under the circumstances it’s tragically comic. As I said, Kempowski keeps the reader at arm’s length, that’s why there isn’t a character I loved but there were two I genuinely disliked. One of them was Peter. I would love to know if anyone who read this had a similar reaction. The more I approached the end, the more I disliked this kid. Such a cold fish.

I’m so glad that I chose this novel for the readalong because it’s not only powerful but important. It tells a story that needed to be told and does so masterfully. Raising awareness for a tragedy, making characters come to life on the page, but not bang your readers over the head or traumatize them – that’s no mean feat.

Other reviews

*******

All For Nothing is the fifth book in the Literature and War Readalong 2016. The list for next year’s Literature and War Readalong will be published in December. Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including the book blurbs can be found here.