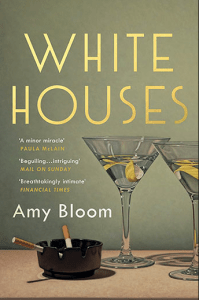

I’m not that familiar with most of the pre-Reagan American presidents and even less with their respective wives, but Eleanor Roosevelt was someone who had piqued my curiosity, years ago, as a teenager. I read a terrific book by Gloria Steinem, called a Book of Self Esteem and she made a comparison between Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Mead. Both women were highly intelligent and successful, but not exactly known for their conventional beauty. As Steinem showed, Mead couldn’t have cared less, while Roosevelt, when asked by an interviewer, whether she had any regrets looking back on her life said: “Just one. I wish I had been prettier.” This struck me as incredibly sad and touched me because it was so frank. I also wondered, what kind of life she thinks she’d have had if she had been prettier. After all, she was married to one of the most popular US presidents. When I came across Amy Bloom’s latest novel White Houses and saw it was about her relationship with Lorena Hickock, I remembered the Steinem book and picked it up. I wasn’t surprised to find out that Eleanor Roosevelt’s looks were also an important topic in this novel.

Of course, White Houses, is a novel, not a nonfiction book, so we have to assume Bloom took some liberties, nonetheless it was fascinating for many reasons. I had an idea of president Roosevelt, like many do, and while I still believe he was one of the better presidents, I don’t think he was that good a man. At least not, judging by this novel. Not only was he a philanderer but quite cruel to his mistresses. When they had served their purpose, he dropped them like a hot potato. But this is only a tiny part of what this book is about.

He was the greatest president of my life-time and he was a son of a bitch every day. His charm and cheer blinded you, made you deaf to your own thoughts, until all you could do was nod and smile, while the frost came down, killing you were you stood. He broke hearts and ambitions across his knee like bits of kindling and then he dusted off his hands and said, Who’s for cocktails? If Missy’s stroke hadn’t killed her, Franklin’s cold heart would have.

White Houses is told by Lorena Hickock, a journalist and writer who seems to have had a love affair with Eleanor Roosevelt. Quite a passionate affair, as it seems. They were drawn to each other physically, emotionally, and intellectually.

While she may not have been a great beauty, Eleanor was very attentive and caring, which endeared her to people.

We love the attentiveness of powerful people, because it’s such a pleasant, gratifying surprise, but Eleanor was not a grand light shining briefly on the lucky little people. She reached for the soul of everyone who spoke to her, every day. She bowed her head towards yours, as if there was nothing but the time and necessary space for two people to briefly love each other.

For many years, Hickock lived with the Roosevelts at the White House. Just like Eleanor accepted her husbands affairs, he seems to have accepted that his wife had hers.

We learn a lot about Lorena Hickock who came from a dirt poor family, was abused by her father and later, during the depression, abandoned. It’s remarkable that she was able, in spite of her hardships, to get a good education and become one of the first female journalists who covered important cases, like that of the Lindbergh baby.

Eleanor came from a totally different background but there’s still a lot of tragedy there. Even though she had six children, she was only really attached to one and he died shortly after his birth. The other kids were brought up by Franklin’s mother, the bossy clan matriarch with whom Eleanor didn’t get along too well. It seems to have been clear for everyone that motherhood was never Eleanor’s calling. And she hated having sex with her husband. It’s sad to think that she still had to go through so many pregnancies.

Since they were public figures, it’s easy to imagine how difficult the relationship between Lorena and Eleanor was. Maybe it was because of that or because of other reasons, but they slowly drifted apart. The book begins right after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death and then moves back and forth in time. The short period after her husband’s death, marks also the end of the love story between Eleanor and Lorena. Why? We don’t know.

White Houses is a elegantly written novel. It’s fascinating and has some wonderful scenes that I enjoyed a lot. The relationship between the women is very affectionate.

We drove to a cabin overlooking the ocean at dusk and unpacked before dark. We shared a brandy and the last of the pretzels and stood in our nightclothes on the little porch, the big quilt around us. The mottled, bright white moon pulled the tide like a silver rug, onto the dark pebbled beach. It should have been a starry sky, but it was deep indigo, like the sea below, with nothing in it but the one North Star.

What I found very well done was the way Bloom described the White House. It is, after all, not only a famous house, but a place where a family, their friends, and entourage live, in other words, it is someone’s home. And that aspect of home, is well captured.

While the novel had many interesting elements, I was a little disappointed. I was left with too many questions and felt I would have done better to pick up a biography. But maybe that’s unfair, as I didn’t regret reading it. Both women are so fascinating and the book manages to show what a complex person the president was.

They loved him. History should show him to be a great man, a great leader, a silver-tongued con man and a devil with women, but if it doesn’t show that they adored him, it’s not telling the truth.

And it does its title justice. It evokes both sides of the White House – the public place and the home of a family.