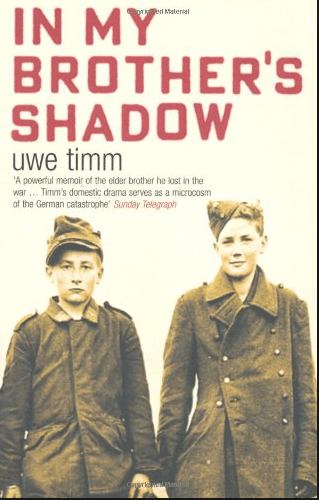

Maybe you’ve never heard of Timm’s novella The Invention of Curried Sausage. If you haven’t, do yourself a favour and get it because it’s marvellous. Possibly because I loved that novella so much, I stayed away from In My Brother’s Shadow – Am Beispiel meines Bruders, although I’d been keen on reading it since it came out in 2003. There’s not one reader or critic who doesn’t think it’s essential reading. But we all know how it goes – everyone praises something, and one has read another book by an author that one loved . . . I’m glad I finally overcame my reluctance because if ever a book was essential reading – then it’s this one. And for many reasons, not only as a brilliant WWII and post-war memoir.

In his memoir In My Brother’s Shadow, Timm doesn’t only try to reconstruct his brother’s life and find out who he really was, but examines his own family and the German post-war society. Timm was born in 1940, the third and last child of his parents. His sister and brother were both over sixteen years older. His brother Karl-Heinz was his father’s favourite. When Karl-Heinz was severely wounded and later died in 1943, on the Eastern Front, in the Ukraine, his father was devastated. The older son was everything he’d wished for. He would take over his business. He was courageous and heroic, unlike little Timm who’s squeamish and dreamy.

Although soldiers weren’t allowed to write a diary, Karl-Heinz did and after he died of his wounds, it was sent back to his parents.

When he’s almost sixty and both of his parents and sister dead, Uwe Timm, rereads the diary and the brother’s letters and decides to write this memoir.

It is clear from the beginning that he doesn’t consider his brother to be a hero. He’s too shocked by some of the diary entries. They are cold and devoid of any compassion with the soldiers and civilians he kills. Karl-Heinz is a member of the SS Panzer Division Totenkopf (Skull and Crossbones). One of the SS’s notorious elite divisions. But what shocks Timm even more, and that’s because it’s also part of the post-war mindset, are the omissions. He knows his brother was present when some of the most horrific extermination operations went on, but he doesn’t mention anything. And in the end, he even stops writing his diary because, as he writes, it doesn’t make sense to write about awful things.

Reading Timm’s account, you can feel that he was ashamed and horrified that he had a brother like this. And he’s ashamed and horrified because of the way people spoke right after the war. Many found it perfectly OK that Jews were killed and were only angry about losing the war. Many others said they “didn’t know” but it was clear they had only chosen not to know.

The silence and passivity of the masses disgusted Timm. He also found out that many soldiers were given a choice whether they wanted to be part of a firing squad or not. Hardly anyone said no. Interestingly though, saying no, had absolutely no consequences. They didn’t choose to fire people because they were scared but simply because they wanted to.

Timm also explores his father’s authoritarian education methods which were pretty typical for that time. Kids had to obey and if they didn’t they were slapped, hit or worse. Psychologists have found out a long time ago that this “black pedagogy” as it is called was one of the reasons why Hitler and Nazism were so successful.

While the book is harsh on his family and many other Germans, it still captures the suffering. His family, like so many others, lost everything when Hamburg was destroyed in ’43. For many years they lived in a cellar.

In My Brothers’ Shadow is also amazing as a book about writing a memoir. What it means to dig deeper and find family secrets. It’s not surprising, he was only able to write about everything so honestly, after his parents and sister were dead.

Uwe Timm is a wonderful, stylish writer that’s why this memoir has many poetic elements. It is a fascinating and touching story of a German family.

One thing that Timm’s elegant and poignant memoir illustrates admirably well – silence is political. Looking the other way is not innocence it’s complicity. This should be self-evident, unfortunately, it wasn’t then and it’s still not now. I’m glad I finally read this memoir. Especially just after Kempowski’s novel. They are great companion pieces.