Although I don’t really stick to my plans these days, I was still tempted to make a list of possible choices for German Literature Month because in the past years my lists helped others find books. I’ll attempt to read a mix of translated and not yet translated books but all by authors known in the English-speaking world.

I started to read Walter Benjamin’s essay collection Denkbilder. Many of the essays can be found in the collection Reflections. Benjamin was a philosopher, essayist, memoirist and modernist writer, who tragically took his own life in 1940, in France, when he knew he wouldn’t be able to escape the Nazis. He has written a lot of influential books like The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Another classic, Thomas Mann’s novella of a young artist, Tonio Kröger.

Another modernist writer and memoirist, just like Walter Benjamin. Elias Canetti’s The Tongue Set Free is a childhood memoir, written in a dense poetic prose.

Judith Hermann has just published her fourth book. I loved her two short story collections and appreciated Alice and now I’m curious to find out how much I’ll like her novel which just came out in Germany.

I bought Judith Schalansky’s The Giraffe’s Neck when it was published in Germany, two years ago. Now it has finally been translated.

Here’s the blurb

Adaptation is everything, something Frau Lomark is well aware of as the biology teacher at the Charles Darwin High School in a country backwater of the former East Germany. It is the beginning of the new school year, but, as people look west in search of work and opportunities, its future begins to be in doubt.

Frau Lohmark has no sympathy for her pupils and scorns indulgent younger teachers who talk to their students as peers, play games with them, or (worse) even go so far as to have ‘favourites’. A strict devotee of the Darwinian principle of evolution, Frau Lohmark believes that only the best specimens of a species are fit to succeed. But now everything and everyone resists the old way of things and Inge Lohmark is forced to confront her most fundamental lesson: she must adapt or she cannot survive.

Written with cool elegance and humane irony, The Giraffe’s Neck is an exquisite revelation of a novel, and what the novel can do, that will resonate in the reader’s mind long after the last page has been turned.

Michael Kumpfmüller has already published a few novels to high acclaim. Some have been translated. The Glory of Life is his latest book and tells the story of Kafka’s last year, during which he fell in love with Dora Diamant. I started reading it and the writing is luminous and lyrical.

The translation of Ferdinand von Schirach’s latest novel Tabu – The Girl Who Wasn’t There will be published in January. He’s another author whose every book I tend to read.

Sebastian von Eschburg, scion of a wealthy, self-destructive family, survived his disastrous childhood to become a celebrated if controversial artist. He casts a provocative shadow over the Berlin scene; his disturbing photographs and installations show that truth and reality are two distinct things.

When Sebastian is accused of murdering a young woman and the police investigation takes a sinister turn, seasoned lawyer Konrad Biegler agrees to represent him – and hopes to help himself in the process. But Biegler soon learns that nothing about the case, or the suspect, is what it appears. The new thriller from the acclaimed author of The Collini Case, The Girl Who Wasn’t There is dark, ingenious and irresistibly gripping.

I’ve almost finished this collection of Ferdinand von Schirach’s essays. Some are interesting, some, like the one of smoking, annoyed me quite a bit, but overall they are worth reading.

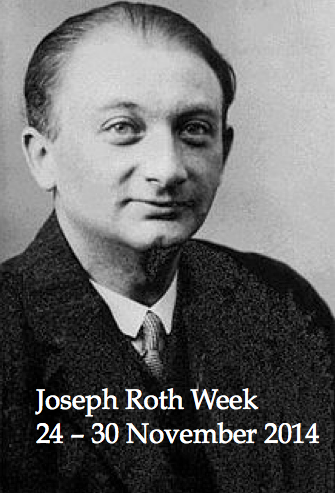

Since I’m hosting a Joseph Roth Week I’ll be reading at least two of his novels. One of them is our readalong title Flight Without End.

Flight Without End, written in Paris, in 1927, is perhaps the most personal of Joseph Roth’s novels. Introduced by the author as the true account of his friend Franz Tunda it tells the story of a young ex-office of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the 1914- 1918 war, who makes his way back from captivity in Siberia and service with the Bolshevik army, only to find out that the old order, which has shaped him has crumbled and that there is no place for him in the new “European” culture that has taken its place. Everywhere – in his dealings with society, family, women – he finds himself an outsider, both attracted and repelled by the values of the old world, yet unable to accept the new ideologies.

The Emperor’s Tomb might be the second choice.

The Emperor’s Tomb is a magically evocative, haunting elegy to the vanished world of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and to the passing of time and the loss of youth and friends. Prophetic and regretful, intuitive and exact, Roth’s acclaimed novel is the tale of one man’s struggle to come to terms with the uncongenial society of post-First World War Vienna and the first intimations of Nazi barbarities.

Jan Costin Wagner is a German crime author whose books are set in Finland. A very unique mix. I’m reading the third in his Kimmo Joentaa series The Winter of the Lions and like it so much, I already got another one. I’m particularly fond of the writing. It’s so sparse and dry. Decidedly more literary than mainstream.

Every year since the tragic death of his wife, Detective Kimmo Joentaa has prepared for the isolation of Christmas with a glass of milk and a bottle of vodka to arm himself against the harsh Finnish winter. However, this year events take an unexpected turn when a young woman turns up on his doorstep.

Not long afterwards two men are found murdered, one of whom is Joentaa’s colleague, a forensic pathologist. When it becomes clear that both victims had recently been guests on Finland’s most famous talk show, Kimmo is called upon to use all his powers of intuition and instinct to solve the case. Meanwhile the killer is lying in wait, ready to strike again…

In Kimmo Joentaa, prizewinning author Jan Costin Wagner has created a lonely hero in the Philip Marlowe mould, who uses his unusual gifts for psychological insight to delve deep inside the minds of the criminals he pursues.

Silence is Wagner’s second Kimmo Joentaa novel.

A young girl disappears while cycling to volleyball practice. Her bike is found in exactly the same place that another girl was murdered, thirty-three years before. The original perpetrator was never brought to justice – could they have struck again? The eeriness of the crime unsettles not only the police and public, but also someone who has been carrying a burden of guilt for many years…

Detective Kimmo Joentaa calls upon the help of his older colleague Jetola, who worked on the original murder, in the hope that they can solve both cases. But as their investigation begins, Kimmo discovers that the truth is not always what you expect.

I’m also tempted by Cornelia Funke’s ghost story Ghost Knight, set in and around Salisbury Cathedral.

Eleven-year-old Jon Whitcroft never expected to enjoy boarding school. He never expected to be confronted by a pack of vengeful ghosts either. And then he meets Ella, a quirky new friend with a taste for adventure…

Together, Jon and Ella must work to uncover the secrets of a centuries-old murder, while being haunted by ghosts intent on revenge. So when Jon summons the ghost of the late knight Longspee for his protection, there’s just one question – can Longspee really be trusted? A thrilling tale of bravery, friendship – and ghosts!

These are the plans for the translated authors/books, but I might also read some of those that haven’t been translated yet, like Keto von Waberer.

Have you read any of these books? What are you’re plans?