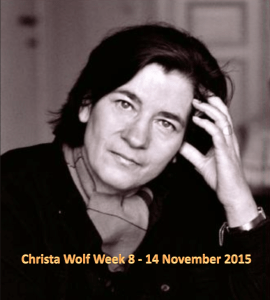

Today begins Christa Wolf Week and I’ve already spotted a few posts here and there. Christa Wolf was one of the most important writers from East Germany. Huge crowds came to her readings. She was considered controversial after the unification because she never openly criticized the values of the regime. She was also accused of having been a Stasi informant. It seems however that she wasn’t collaborating the way the authorities wanted and that she was closely watched herself. Given the complexity of the subject, I’m grossly simplifying here.

I was hoping to review at least two of her books but I won’t manage much more than The Quest for Christa T., which I find beautiful, fascinating, and annoying in equal measures. It doesn’t have a lot in common with the other books I read by her and which I liked, or even loved. The first book by Wolf I read was Cassandra and I still think it’s one of her greatest books and one of the greatest retellings of a myth. I also liked They Divided the Sky because it allows us the see the former German Democratic Republic through someone’s eyes who really stood behind its ideals. The one I truly loved was No Place on Earth that tells a fictitious meeting of the writers Karoline von Günderrode and Heinrich von Kleist, who both committed suicide a few years after the imagined meeting took place.

Other books by her that are important are Medea, A Day a Year and A Model Childhood.

What are you reading this week? Do you have a favourite Christa Wolf book?