Some Literature and War Readalong lists took a long time. Not this one. The only thing that took some time was deciding whether I wanted to choose twelve books like I used to or only five like I did in the last two years. In the end, I decided for a compromise and that’s why this year’s list has ten titles, three of which will be the readalong books for May. Usually the summer months and the end of December have never been ideal dates, so I’m skipping those.

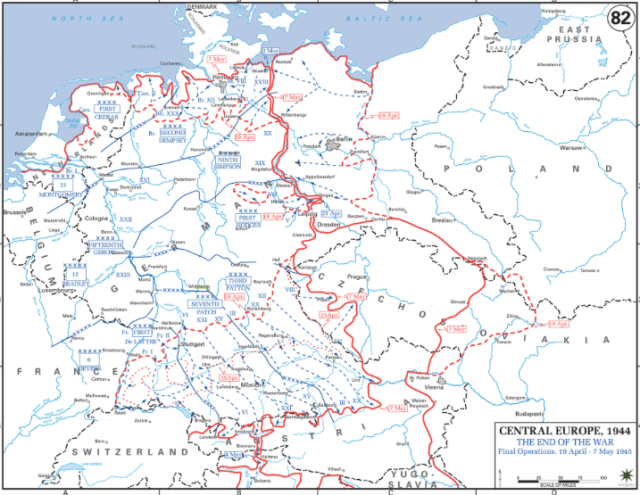

Now to my book choices. As you will see, with one exception, they are all focussing on WWII. I always strive for diversity and this year is no exception. There are books from five different countries on the list. Every year I include American novels, this year, to make a statement, I chose two Native American writers. Three of the other novels are French, one is Czech, and one German. May’s choice(s) are special because, for the first time, I decided to include poems. We will be reading and discussing British war poems. Some from poets who wrote during WWI, some from contemporary poets like Vanessa Gebbie and Caroline Davies. I’d like to thank Caroline for suggesting I include poems.

Here are the books and their blurbs.

January, Tuesday 31

House Made of Dawn by N. Scott Momaday, 208 pages, US 1966, WWII

The magnificent Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of a stranger in his native land

A young Native American, Abel has come home from a foreign war to find himself caught between two worlds. The first is the world of his father’s, wedding him to the rhythm of the seasons, the harsh beauty of the land, and the ancient rites and traditions of his people. But the other world — modern, industrial America — pulls at Abel, demanding his loyalty, claiming his soul, goading him into a destructive, compulsive cycle of dissipation and disgust. And the young man, torn in two, descends into hell.

February, Tuesday 28

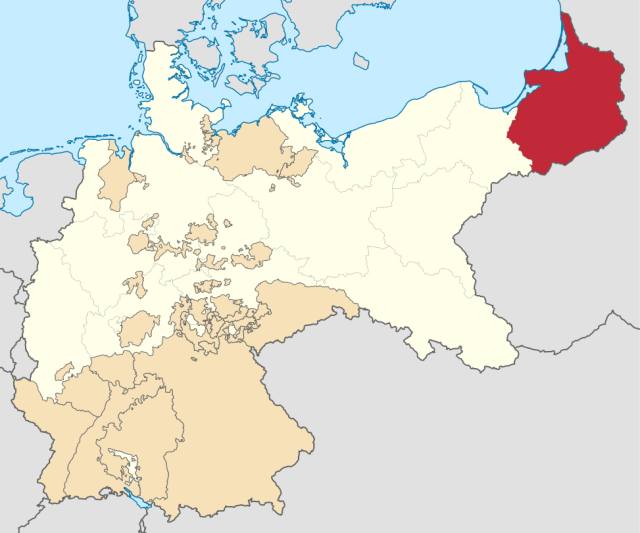

Magnus by Sylvie Germain, 190 pages, France 2005, WWII

Magnus is a deeply moving and enigmatic novel about the Holocaust and its ramifications. It is Sylvie Germain’s most commercially successful novel in France. It was awarded The Goncourt Lyceen Prize. Magnus’s story emerges in fragments, with the elements of his past appearing in a different light as he grows older. He discovers the voices of the deceased do not fall silent. He learns to listen to them and becomes attuned to the echoes of memory.

March, Friday 31

Closely Observed Trains – Ostře sledované vlaky by Bohumil Hrabal, 96 pages, Czech Republic 1965, WWII

For gauche young apprentice Milos Hrma, life at the small but strategic railway station in Bohemia in 1945 is full of complex preoccupations. There is the exacting business of dispatching German troop trains to and from the toppling Eastern front; the problem of ridding himself of his burdensome innocence; and the awesome scandal of Dispatcher Hubicka’s gross misuse of the station’s official stamps upon the telegraphist’s anatomy. Beside these, Milos’s part in the plan for the ammunition train seems a simple affair.

April, Friday 28

La douleur – The War by Marguerite Duras, 217 pages, France 1985, WWII

This 1944 diary of a young Resistance member, written during the last days of the French occupation and the first days of the liberation, is only now being published – Duras says she forgot about it during the intervening years, and only recently rediscovered it in a cupboard. The loneliness and ambivalence of love and war have appeared in Duras’ work before, from The Lover to Hiroshima Mon Amour, in which a Frenchwoman reveals to her Japanese lover, after the bomb, that she was tortured and imprisoned in postwar France for her affair with a German soldier. In the first section of The War, Duras the heroine waits for her husband to return from the Belsen concentration camp. When De Gaulle (“by definition leader of the Right – “) says, “The days of weeping are over. The days of glory have returned,” Duras says, “We shall never forgive him.” It’s because he’s denying the people’s loss. When her husband returns, she has to hide the cake she baked for him, because the weight of food in his system can kill. (We are spared no detail of his physical degradation, even to being told the color of his stools.) When he is stronger, she tells him she is divorcing him to marry another Resistance member. In the second section, set earlier, at the time of her husband’s arrest, a Gestapo official plays a cat-and-mouse game with Duras, to whom he’s attracted, preying on her desperation to help her husband. In the third section, post-liberation, she switches roles, becomes an interrogator as Resistance members torture a Nazi informer. She also half-falls in love (with characteristic Duras dualism) with a young prisoner who childishly joined the collaborationist forces out of nothing more than a passion for fast cars and guns. In her preface, Duras says it “appalls” her to reread this memoir, because it is so much more important than her literary work. Certainly, like everything she has written in her spare, impassive voice, the book is at once elegant and brutal in its honesty: in her world, we are all outcasts, and the word “liberation” is never free of irony. A powerful, moving work. (Kirkus Reviews) –This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

May, Wednesday 31

Poems of the Great War

Published to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of Armistice, this collection is intended to be an introduction to the great wealth of First World War Poetry. The sequence of poems is random – making it ideal for dipping into – and drawn from a number of sources, mixing both well-known and less familiar poetry.

Voices from Stone and Bronze by Caroline Davies

A moving, honest and never sentimental collection that gives a voice to London’s many war memorials.

In her second poetry collection Caroline Davies turns her attention to the War Memorials of London. Voices from Stone and Bronze brings to life those who fought and died and those who survived, including some of the sculptors who had themselves come through trench warfare to a changed world.

Meticulously researched and deeply humane, these narrative poems apply a lyrical sensibility without sentimentalism; a deeply affective collection.

Memorandum by Vanessa Gebbie

Memorandum is a haunting collection of poems that summons voices from the shadows of the First World War. Vanessa Gebbie transforms prosaic records of ordinary soldiers, and the physical landscape of battles, war graves and memorials, into poignant reflections on the small and greater losses to families and the world. Vanessa Gebbie is a writer of prose and poetry. Author of seven books, including a novel, short fictions and poetry, her work has been supported by an Arts Council England Grant for the Arts, a Hawthornden Fellowship and residencies at both Gladstone’s Library and Anam Cara Writers’ and Artists’ Retreat. She teaches widely. http://www.vanessagebbie.com “From the idea of a shell reverting to its unmade, peaceful state to dead men buried in Brighton and France being mourned by their mother in Glasgow … heartrending images such as the Tower of London’s ceramic poppies seen as callow recruits, doubts about a corpse’s identity and how dregs at the bottom of a cup can be reminiscent of the deadly Flanders mud. This is a modern view, wise and compassionate, of Europe’s fatal wound.” Max Egremont, author of Siegfried Sassoon and Some Desperate Glory, The First World War the Poets Knew “Vanessa Gebbie is that rare breed of poet who understands the trials and tribulations of the ordinary Tommy.” Jeremy Banning, military historian and researcher, battlefield guide “The dead who linger around memorials and battlefields slowly step again into the light. History may remember them collectively, but Gebbie’s achievement is to present, with sensitivity and without sentimentality, lives rooted in the particular rhythms of hometowns, families, and memories.” John McCullough, author of Spacecraft and The Frost Fairs “These poems rise like ghosts from a scarred landscape.” Caroline Davies, author of Convoy

September, Friday 29

Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko, 243 pages, US 1977, WWII

The great Native American Novel of a battered veteran returning home to heal his mind and spirit

More than thirty-five years since its original publication, Ceremony remains one of the most profound and moving works of Native American literature, a novel that is itself a ceremony of healing. Tayo, a World War II veteran of mixed ancestry, returns to the Laguna Pueblo Reservation. He is deeply scarred by his experience as a prisoner of the Japanese and further wounded by the rejection he encounters from his people. Only by immersing himself in the Indian past can he begin to regain the peace that was taken from him. Masterfully written, filled with the somber majesty of Pueblo myth, Ceremony is a work of enduring power. The Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition contains a new preface by the author and an introduction by Larry McMurtry.

October, Tuesday 31

Suite Française by Irène Nemirovsky, 432 pages, France 1942, WWII

Set during the year that France fell to the Nazis, Suite Française falls into two parts. The first is a brilliant depiction of a group of Parisians as they flee the Nazi invasion; the second follows the inhabitants of a small rural community under occupation. Suite Française is a novel that teems with wonderful characters struggling with the new regime. However, amidst the mess of defeat, and all the hypocrisy and compromise, there is hope. True nobility and love exist, but often in surprising places.

Irène Némirovsky began writing Suite Française in 1940, but her death in Auschwitz prevented her from seeing the day, sixty-five years later, that the novel would be discovered by her daughter and hailed worldwide as a masterpiece.

November, Wednesday 29

The Oppermanns – Die Geschwister Oppermann by Lion Feuchtwanger, 416 pages, Germany 1934, WWII

First published in 1934 but fully imagining the future of Germany over the ensuing years, The Oppermanns tells the compelling story of a remarkable German Jewish family confronted by Hitler’s rise to power. Compared to works by Voltaire and Zola on its original publication, this prescient novel strives to awaken an often unsuspecting, sometimes politically naive, or else willfully blind world to the consequences of its stance in the face of national events — in this case, the rising tide of Nazism in 1930s Germany. The past and future meet in the saga of the Oppermanns, for three generations a family commercially well established in Berlin. In assimilated citizens like them, the emancipated Jew in Germany has become a fact. In a Berlin inhabited by troops in brown shirts, however, the Oppermanns have more to fear than an alien discomfort. For along with the swastikas and fascist salutes come discrimination, deceit, betrayal, and a tragedy that history has proved to be as true as this novel’s astonishing, profoundly moving tale.

*******

I’m looking forward to reading these books and hope that some of you might be tempted to join me and join the discussions.

For those who are new to this blog – you can either read the book and just join the discussion or you can post a review on your blog/Goodreads . . . as well. I post my review on the announced date and will link to anyone else’s review. The discussion normally begins that day and lasts several days.