I wrote about one of Eduard von Keyserling’s novellas during GLM 2013 –here. Back then, not one of his books had been translated into English and that was such an incredible shame. Meanwhile, his masterpiece Die Wellen – Waves has been translated and published by Dedalus European Classics. As I wrote in that post, von Keyserling is often compared to Fontane because they are from the North and both set their novels in the Northern parts of Germany. It’s a very unfortunate comparison because the era and writing style are so different. Both are elegant writers, but von Keyserling is much more like Schnitzler than Fontane. He’s a typical impressionist writer. He has something very Austrian and when one knows a few things about his life, that’s no coincidence. He was born at Castle Tels-Paddern (now in Latvia), Courland Governorate, then part of the Russian Empire, but then moved to Vienna and later to Munich.

Maybe Waves wasn’t a success – I never saw it reviewed on any blogs – because that remained the only official translation. There’s good news though, as Tony from Tony’s Reading List actually went and translated first the book I reviewed in 2013 – Schwüle Tage – Sultry Days and then two other short works, which you can all find here.

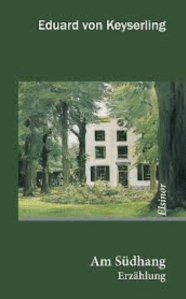

Sadly, Am Südhang – On Southern Slopes, the novella I read on my beautiful rainy reading day last week, hasn’t been translated. As with everything I’ve ever read by von Keyserling – it’s a shame. He’s such a brilliant writer.

Am Südhang opens with Karl Erdmann von West-Wallbaum in a carriage on his way to his parent’s estate where he will spend his summer. He has just been made Lieutenant and thinks that this rise will mean people will take him more seriously. He can hardly wait to arrive as the summers on his parent’s estate are always so beautiful. And he is always in love. Always with the same woman, Daniela, a friend of his mother, who is much younger and divorced. Every summer she’s the centre of all the men’s attention as she’s beautiful, intelligent, and likes to charm. It’s both painful and delicious to be in love with her, as Karl Erdmann muses, and he’s looking forward to lying in the grass and dream of her all day long.

But that isn’t the only thing he’s looking forward to. On the estate, with his family, his parents and siblings, he lives a life of sheltered ease and luxury which makes him languorous and lazy. While he can be hard and cynical in the outer world, during summer he’s like sensitive, thin-skinned fruit that grows on southern slopes.

It wouldn’t be a von Keyserling novel if things stayed light and harmonious. There’s always a dark undercurrent and tragedy and this story is no exception. Even though he doesn’t take it very seriously, the duel that awaits Karl Erdmann casts a dark shadow. And there’s also the deep sadness of the private tutor who, like everyone else, is in love with Daniela.

It’s a beautiful novella. Rich in emotions and descriptions. Nature and the weather always play important parts, mirroring the feelings of the protagonists. In this story, the garden descriptions are so very lush. Von Keyserling paints with words. He captures scents and sound, colours and forms. We sit next to Karl Erdmann in his carriage and feel the cool shade under the trees, hear the soft rustling of the dew in the leaves. We can see the family waiting for Karl Erdmann’s arrival, the women in their white summer dresses standing on the stairs.

The only thing that was hard to read was the duck hunting. It’s always part of these novels set among the upper classes. And it’s always terrible. It was over quickly, but still made me sad.

There is some criticism of the way of life described, but mostly von Keyserling just captures a moment in time. It’s a dying society but when he wrote this novella, in 1916, it was still very much alive.

I hope this will be translated because it’s so amazing. I’m sure most of us can relate to the magic of summer holidays when you’re still a child or very young. Those hot, languorous, carefree days, mostly spent outdoors unless summer rains kept you in.

If you haven’t read von Keyserling yet, do yourself a favour and read Waves or some of Tony’s translations. I’m adding the link to them here again.

Most of his novellas were translated into French – here’s a link to the collected works.

The cover of the German edition shows a painting of Max Liebermann, Landhaus in Hilversum (1901). It’s the perfect choice for this book.