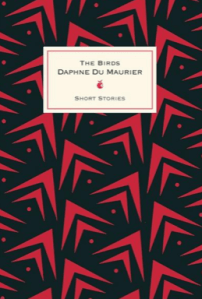

Today begins Heavenali’s Daphne du Maurier week. I knew I wanted to participate but wasn’t sure how to fit it into my A Post a Day in May project. But then I had an idea that appealed to me a lot. Why not reread one of her most famous stories, The Birds, and compare it to the Hitchcock movie. And that’s what I did a couple of days ago.

April and May have been very hot here in Switzerland, sunny and with temperatures around 27°C. Not so two days ago when I finally reread and rewatched The Birds. That day was cool and rainy. Perfect weather for this creepy tale.

The short story The Birds is set in the country, near the sea. Nat is a farmhand. On the day the story begins, he notices the birds’ unusual behaviour. It is the beginning of December and the weather has changed abruptly overnight. From a mellow autumn, it is has turned into an icy winter. Could this have something to do with the birds? Is this why they flock together and thousands of seagulls cover the sea like a giant wave? And then they start to attack. Nat and his family have to barricade themselves in their house as the birds get more and more aggressive, trying to enter the house through the windows, the chimney.

I enjoyed this story so much. It’s rich in descriptive details and atmosphere. Creepy, eerie, like a good ghost story, even though that’s not what this is.

One element resonated with me a lot. While they are locked into their house, Nat and his family try to find out what’s going on, whether the government will send help, what they say is happening, and what they should do. A bit like now, and Nat and his wife get very annoyed when they realize the government is clueless. Just like now, they are absolutely no help and offer no guidance in a massive crisis.

After finishing the short story, I then watched the movie. I know I watched it many years ago and must say, the movie I rewatched had absolutely nothing to do with what I remembered of it.

Unlike the story, the movie is set in a small town. I didn’t remember how much story Hitchcock added to du Maurier’s story. Hers is very pared down and atmospheric. But Hitchcock’s film starts like a screw ball comedy. A young rich woman meets a lawyer in a bird shop in San Francisco. She then decides to bring him the love birds he wanted for his sister to his house on Bodega Bay, outside of San Francisco. Like in any screw ball comedy, they try to pretend they are mutually not interested. They tease each other and what follows is a humorous back and forth. But then a seagull attacks the woman and the story changes.

I must say, I was disappointed in the movie. It lacked atmosphere, almost felt like two films in one. Of course, for its time it’s a great movie but I liked the short story so much better, found it so much more effective. Not for one second did I find the movie eerie. If I had watched this a few weeks after reading the story or without even rereading the story, my reaction would have been different, I’m sure. It’s obvious that Hitchcock only used the story as an inspiration. I read once that he always started with an image and this is possibly the case here too. He was fascinated by the idea of all those birds gathering. And for its time, those attack scenes are well done. That he added a love story and complex characters, is an interesting choice. I like that he chose to go deeper, introduce us to complex characters with backstory, but I’m not sure why he chose to start with some type of screw ball comedy. Maybe he hoped the contrast would intensify the horror that follows? I am probably not doing it justice. Someone who doesn’t know the story, might find the movie terrifying.

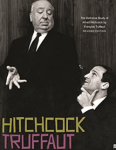

It was certainly an interesting experience to compare the two and made me realize that I want to read more of her, and definitely rewatch many of his movies and discover those I don’t know yet. Luckily, I have two Hitchcock collections here. Over twenty movies in total. And I also own Truffaut’s book on Hitchcock, which I should finally read.

Which is your favourite du Maurier book? And which is your favourite Hitchcock movie?