Thanks to the generosity of different publishers, Lizzy and I are able to give away a number of wonderful books.

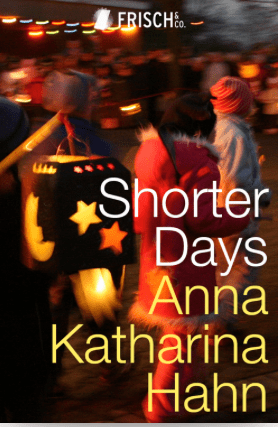

I’m particularly pleased to give away a copy of the e-book of Anna Katharina Hahn’s novel Shorter Days. I’ve often thought that it was sad that her novel hadn’t been translated because I loved it so much. I’ve read it when it came out in Germany, in 2009, at a time when I read far more German than English books. Since then it’s among my top 5 German books of the last decade. I was really happy when I saw that Frisch & Co, an e-book publisher, was going to publish the novel in October.

Here’s the publisher’s blurb

It’s fall in Stuttgart, just before Halloween, and thirty-something mothers Judith and Leonie are safely ensconced in their upscale apartments in one of the city’s best neighborhoods. Judith has squeezed her life into the straitjackets of stay-at-home Waldorf motherhood—no TV, no sweets, nature hikes, and, above all, routine—and marriage to staid university professor Klaus. Leonie is proud of her work at a bank and her husband Simon’s career, though she worries that she’s neglecting her young daughters, and that Simon’s work distracts him from his family. Over the course of a few days, Judith and Leonie’s apparently stable, successful lives are thrown into turmoil by the secrets they keep, the pressures they’ve been keeping at bay, and the waves of change lapping at the peaceful shores of their existence.

Shorter Days is a heartrending exploration of the joys, challenges, and dangers of modern family life.

The second book I am giving away is a nonfiction book, published by Pushkin Press, Maxim Leo’s Red Love: The Story of an East German Family. I haven’t read it but it sounds very interesting.

Here’s the blurb

Growing up in East Berlin, Maxim Leo knew not to ask questions. All he knew was that his rebellious parents, Wolf and Anne, with their dyed hair, leather jackets and insistence he call them by their first names, were a bit embarrassing. That there were some places you couldn’t play; certain things you didn’t say.

Now, married with two children and the Wall a distant memory, Maxim decides to find the answers to the questions he couldn’t ask. Why did his parents, once passionately in love, grow apart? Why did his father become so angry, and his mother quit her career in journalism? And why did his grandfather Gerhard, the Socialist war hero, turn into a stranger?

The story he unearths is, like his country’s past, one of hopes, lies, cruelties, betrayals but also love. In Red Love he captures, with warmth and unflinching honesty, why so many dreamed the GDR would be a new world and why, in the end, it fell apart.

“Tender, acute and utterly absorbing. In fine portraits of his family members Leo takes us through three generations of his family, showing how they adopt, reject and survive the fierce, uplifting and ultimately catastrophic ideologies of 20th-century Europe. We are taken on an intimate journey from the exhilaration and extreme courage of the French Resistance to the uncomfortable moral accommodations of passive resistance in the GDR.

“He describes these ‘ordinary lies’ and contradictions, and the way human beings have to negotiate their way through them, with great clarity, humour and truthfulness, for which the jury of the European Book Prize is delighted to honour Red Love. His personal memoir serves as an unofficial history of a country that no longer exists… He is a wry and unheroic witness to the distorting impact – sometimes frightening, sometimes merely absurd – that ideology has upon the daily life of the individual: citizens only allowed to dance in couples, journalists unable to mention car tyres or washing machines for reasons of state.” Julian Barnes, European Book Prize

With wonderful insight Leo shows how the human need to believe and to belong to a cause greater than ourselves can inspire a person to acts of heroism, but can then ossify into loyalty to a cause that long ago betrayed its people.” Anna Funder, author of Stasiland

I’d like to thank Frisch & Co. and Pushkin Press for their generosity.

If you’d like to enter the giveaway, leave a comment, indicating for which book you’d like to enter. You can enter for both, of course.

Don’t miss visiting Lizzy’s site as she’s giving away titles from other publishers.

The giveaway is open internationally. The winners will be announced on Sunday, 5th October 2014.

THIS GIVEAWAY IS NOW CLOSED: THE WINNERS HAVE BEEN ANNOUNCED.