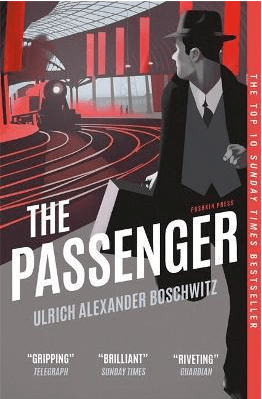

In 2015, Peter Graf, the German editor of The Passenger, read Boschwitz’s manuscript for the first time. The Passenger was written in 1939, right after the November pogroms described in the novel; its English translation came out the same year in the UK. The US edition followed in 1940. Given the status of the writer, a German Jew who fled Nazi Germany in 1935, and the nature of the story, it never stood a chance of being published in Germany at the time. But post-war Germany was equally reluctant to publish the novel, even though Heinrich Böll was one of its most enthusiastic supporters. It took many decades more until Peter Graf decided to edit and publish the book. The English retranslation followed and finally The Passenger became a publishing success. During his lifetime, Boschwitz published another novel. In a Swedish translation, if I’m not mistaken. His third and final manuscript was lost together with the author. In 1942, then only aged 27, Boschwitz was on a ship back from Australia to the UK when they were hit by a German U-Boot.

The Passenger is one of the earliest German books about pre-war Germany and the November pogroms. Boschwitz who was Jewish lived in the UK at the time. He’d fled Germany in 1935 and first went to Paris. Elements of his story and the story of his family are described in the book. The pogroms were a huge shock for him. The Jews who were still in Germany in 1938 were sent to concentration camps, their property was confiscated. Within a few days they lost everything. Many tried to flee but the surrounding European countries were less than welcoming.

Otto Silbermann, the main protagonist of The Passenger, is one of those Jews who lose their company and wealth, and almost get arrested. Panicked, he flees to the train station and boards a train. The first chapters show him chasing an associate who conducts a last transaction for him. The man who isn’t Jewish, cheats him out of most of his fortune, but Silbermann is still left with 40,000 mark, an equivalent of 170,000 Euro. Decidedly enough to start a new life somewhere else. So, purely based on the circumstances, things do not look catastrophic for Silbermann. He saved his life and a small fortune. Moreover, his Arian wife can stay with her brother and his son is safely in Paris. All Silbermann must do is cross the border into Switzerland or Belgium. But while the circumstances aren’t totally against him, Silbermann is his own worst enemy. He waited too long, thinking he wouldn’t have to share the fate of all the other Jews. One gets the impression he doesn’t really see himself as Jewish because he doesn’t look Jewish and isn’t religious. To assume there’s some kind of rationality, albeit a warped one, behind the persecutions, is his biggest error. Like most totalitarian regimes, Nazi Germany has no real reason for its actions; they are purely based on irrational pretexts and scapegoating. Silbermann lived with a false sense of security for too long and once it becomes apparent that he is in danger too, the shock is so immense that he isn’t capable of clear thinking. What the reader witnesses from that moment on, is one failure and one wrong decision after the other.

I’ve read a whole series of WWII books for this GLM (due to personal reasons I couldn’t review them) and this was by far the toughest of them all. It’s so claustrophobic. The atmosphere of rising fanaticism, the way everything closes in on Silbermann is depressing. And the role ordinary people played to support this madness is mindboggling. Silbermann meets a few good Germans, but the vast majority is either actively persecuting Jews, supporting the persecutors, or cowardly looking the other way.

One of the most crucial moments in the book is an encounter between Silbermann and another Jew who is easily recognizable as Jewish. He asks Silbermann for help, and just like some of the Germans Silbermann asked himself, he denies it because he’s scared. This act of cowardice robs him of his last precious belonging – his self-esteem. Until that moment he thought of himself as very different, now, suddenly, he knows he’s not.

The Passenger is an amazing document of a specific moment in Germany’s history. And it’s an amazing portrait of a very flawed man. I was wondering, why Boschwitz chose Silbermann as his protagonist and couldn’t help but wonder whether he wanted to say, that especially the atypical, irreligious Jews who stayed in Germany, unconsciously supported the rising madness in thinking they would be exempt. Or maybe he just wanted to say that it is human nature to go the way of least resistance.

I know that I didn’t do this book justice and so I’m glad several other people who participated in the readalong wrote more eloquent reviews.

I’ll be collecting them here:

I’m taking this opportunity to apologize if I haven’t been very active this year and not visited and commented on your blog posts. Personal circumstances sadly made it impossible.

I just skimmed through your review, because I haven’t finished reading this book yet, Caroline. Just read the first and last passages of your review. I’ll come back later and read your review properly and then comment. Thanks so much for hosting this readalong. I didn’t know that this book was written in 1939 but translated only recently. I thought the book was published just now. Its publishing history is fascinating.

Very interesting history. Karen writes a bit more about. I’m very interested to hear what you thought of it.

I appreciated your review Caroline, and it has made me more interested in the novel. You do a good job on the background of its being published and your questions about the circumstances of those times are so clearly genuine. I admit I haven’t been reading much in the way of German-language literature lately. I did read Twelve Nights by Urs Faes, but it didn’t feel so much like a book that warranted by little Twitter review! Look after yourself, Caroline, in these challenging times. XJ

Thank you for the kind words, Jennifer.

It’s a chilling book. Both sides are shown so well. The panic one one side, the rising fanaticism, the petty or real cruelties. Human nature in all of its forms. More than anything he captures those so well who went along with it, out of cowardice or fear. Xx

Sorry to hear that you have been unwell Caroline. Get well soon. I haven’t read this book. However I did read: My Father’s Keeper: The Children of Nazi Leaders – An Intimate History of Damage & Denial but the linky would not accept t at German Literature Blogspot nor could I leave it in the comments section (plz allow those on wordpress too to comment over there, it only accepts comments from those on blogger) so leaving the link here:

Thank you so much, Neer.

That book sounds very interesting.

I had no idea about the comment problem. I’ll have to tell Lizzy as she’s in charge of the site. I hope she can enter your post. Thank you for participating.

Thanks for posting about this despite personal circumstances, and I hope things improve. I think you’ve picked up on a very important point I may not have made, which is the immediacy of the book and the power that comes through from the proximity to the events it describes. That gives it a particular edge, I think, and I’m just glad it got brought back into print.

Thanks, Karen. I hope so too. It’s a bit of a struggle.

It’s lucky it was reissued because it’s so much more poignant than a historical novel. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that made me experience the rising terror and panic quite like this. It also shows well why many stayed too long. No matter whether they looked Jewish or not.

This sounds excellent, I think I saw it reviewed somewhere else a while back. The claustrophobia you describe really comes across from your review, I can see it might be a tough read.

It is excellent but tough to read. And bewildering. To imagine a whole nation, with few exceptions, accepted to greet each other with Heil Hitler. We know they did but the book shows how absurd it was yet it was embraced. It’s a symbol of the fanatic madness.

I’ll save your review of this novel, Caroline, as I have a copy of it on my shelves and would rather not know anything more about it beforehand. Apologies too for my lack of participation in this year’s GLM. I had intended to read something for it, but unfortunately other priorities got in the way. C’est la vie, as they say… Sorry to hear that you’ve had a difficult month – I hope you’re okay? X

No worries. I would do the same. Very difficult month indeed and it’s not likely to get better soon. Yeah well. Thanks for asking. Xxx

As I mentioned on Karen’s post this is a book that is still on the TBR, but was immediately drawn by the gripping backstory to the writing and publishing of it, and the as you detail, the immediacy of the story itself. Sending you best wishes and hopes that things are better for you soon. Take care.

Thanks, Julé. Difficult times in many ways.

The book is really special, its publishing story just as much as the story. It won’t let you cold, I’m sure.

Thanks for this post Caroline. I read The Passenger just this week and found it a powerful read, with the ratcheting up of that terrible feeling of panic and entrapment.

My pleasure. It’s so powerful. I’m glad you liked it too although ‘like’ might be the wrong word.

This sounds so claustrophobic, quite a stressful read in many ways! Your review and the others I’ve read have definitely put this on my list. I’m sorry to hear that you’re having a tough time Caroline, I hope things improve for you soon. Take care x

I don’t think you’ll regret reading it but possibly it’s one to read at another time. It’s so very dark. Thanks for the wishes, Mme Bibi.

Pingback: German Literature Month XI Author Index – Lizzy's Literary Life

The reason Boschwitz, in the novel The Passenger, likely had Silbermann, an assimilated Jew, believing he would be exempt has to do with how antisemitism has expressed itself historically in Germany.

Before Hitler, Jews were discriminated against only for religious reasons, i.e., for being unwilling to convert to Christianity. But with the specious race classifications underlying Aryanism that the Nazis introduced, assimilated Jews—even those who converted—became discriminated against as well. There was no way this development could have been foreseen by the average, nonideological German before Hitler rose to power in 1933.

Thank you for your review, Caroline. Wishing you much improved health in the new year!

Thank you for the wishes, Susan. It’s true what you’re saying about the persecution of Jews before the Nazis and may well be the reason why he chose an assimilated but it’s also a criticism. The writer was a non religious, assimilated Hew but he and most of his family fled very early.