Tag Archives: Readalong

Literature and War Readalong September 30 2016: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain

Next up in the Literature and War Readalong 2016 is Ben Fountain’s novel on the war in Iraq Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. Billy Lynn is Ben Fountain’s first novel. Before that he was mostly known as a short story writer. Many of his stories were published in prestigious magazines and received prizes (the O.Henry and Pushcart among others). A lot of people who already read this novel, told me how much they liked it. If I’m not mistaken, the book is set in the States and not in Iraq. It’s neither a war zone story, nor a home front story but a story of soldiers who are back home to celebrate a victory, before they will be shipped out again.

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain, 307 pages, US 2012, War in Iraq

Here are the first sentences

The men of Bravo are not cold. It’s a chilly and windwhipped Thanksgiving Day with sleet and freezing rain forecast for late afternoon, but Bravo is nicely blazed on Jack and Cokes thanks to the epic crawl of game-day traffic and limo’s mini bar. Five drinks in forty minutes is probably pushing it, but Billy needs some refreshment after the hotel lobby, where over caffeinated tag teams of grateful citizens trampolined right down the middle of his hangover.

Here’s the blurb:

His whole nation is celebrating what is the worst day of his life

Nineteen-year-old Billy Lynn is home from Iraq. And he’s a hero. Billy and the rest of Bravo Company were filmed defeating Iraqi insurgents in a ferocious firefight. Now Bravo’s three minutes of extreme bravery is a YouTube sensation and the Bush Administration has sent them on a nationwide Victory Tour.

During the final hours of the tour Billy will mix with the rich and powerful, endure the politics and praise of his fellow Americans – and fall in love. He’ll face hard truths about life and death, family and friendship, honour and duty.

Tomorrow he must go back to war.

*******

The discussion starts on Friday, 30 September 2016.

Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including all the book blurbs, can be found here.

James Salter: The Hunters (1956) Literature and War Readalong May 2016

The Hunters was James Salter’s first novel. It is based on his own experience as a fighter pilot during the war in Korea.

The Hunters tells the story of Cleve Connell, an excellent, seasoned pilot who is sent to Korea. Cleve is anxious to get there. He wants to prove himself and become an ace, a fighter pilot who has shot down five enemy planes – MIGs. He knows he’s running against time because he isn’t a young pilot anymore.

One thing he was sure of: this was the end of him. He had known it before he came. He was thirty-one, not too old certainly; but it would not be long. His eyes weren’t good enough anymore. With a athlete, the legs failed first. With a fighter pilot, it was the eyes. The hand was still steady and judgement good long after man lost the ability to pick out aircraft at the extreme ranges. Other things could help to make up for it, and other eyes could help him look, but in the end it was too much of a handicap. He had reached the point, too, where a sense of lost time weighed on him. There was a constant counting of tomorrows he had once been so prodigal with. And he found himself thinking too much of unfortunate things. He was frequently conscious of not wanting to die. That was not the same as wanting to live. It was a black disease, a fixation that could ultimately corrode the soul.

Cleve and every other pilot lives for nothing else but the adrenaline rush of a mission that may bring the possibility to shoot down an MIG and to survive another dangerous mission. The pilots are all competitive but that doesn’t mean they would endanger each other.

They had shot down at least five MIGs apiece. Bengert had seven, but five was the number that separated men from greatness. Cleve had come to see, as had everyone, ho rigid was that casting. There were no other values. It was like money: it did not matter how it had been acquired, but only that it had. That was the final judgement. MIGs were everything. If you had MIGs you were standard of excellence. The sun shone upon you.

Then, one day, Pell arrives. Pell is by far the most competitive pilot Cleve has ever met. And the most reckless. He’s assigned to Cleve’s flight, a small group of pilots of which Cleve’s the leader. Cleve hates him immediately. Not only because he’s so competitive but because he senses he would do anything for a kill and that he’s dishonest. Pell hates Cleve just as much. He’s jealous of his reputation and undermines his authority from the start.

At first, Cleve’s very sure of himself because he’s known to be one of the best pilots but after he returns from many missions, without one single kill, he loses confidence. On top of that, Pell shoots down one enemy plane after the other and, so, killing turns into an obsession for Cleve.

Cleve’s not the only pilot who seems to have forgotten, that ultimately they are in a war. The following quote might explain why this is the case.

They talked for a while longer, mostly about the enemy, what surprisingly good ships they flew and what a lousy war it was. The major repeated that despairingly several times.

“What do you mean, lousy?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Abbott said distractedly, “it’s just no good. I mean what are we fighting for, anyway? There’s nothing for us to win. It’s no good, Cleve, You’ll see.”

The Korean war is often referred to as the “forgotten war” and this sense of not really knowing what they were fighting for, seems to have been almost universal. Many of the pilots who fought in the Korean war, fought during WWII. While they had the sense of having done good in Europe and the Pacific, they often didn’t really understand why they fought in Korea. However, the book doesn’t explore the political or historical dimensions of the war. It only focuses on the drama of the pilots.

The Hunters is an excellent novel and the reader senses that from the beginning. The writing is tight and precise. Salter uses metaphor and foreshadowing with great results. He’s also very good at capturing emotions and moods like in this quote:

He was tired. Somehow, he had the feeling of Christmas away from home, stranded in a cheap hotel, while the snow fell silently through the night, making the streets wet and the railroad tracks gleam.

The book offers a fascinating character study, or rather the study of two characters. And it’s suspenseful. We wonder constantly whether Cleve will make it, become an ace and leave Pell behind or whether Pell will leave him behind for good. And then there’s the almost mythical figure of “Casey Jones”, a Korean Fighter pilot who is so reckless and successful that everybody speaks about him and thinks he’s invincible. Shooting down a pilot like that, would make up for everything else.

I can’t say more as it would spoil this excellent novel. It’s amazingly well written and surprisingly suspenseful. And, as if that was not enough, the end is unexpected and satisfying.

The book comes with a foreword, for which I was glad as it’s key to understand in what formations the pilots flew and to know what the characteristics of the respective planes were. There’s a great scene towards the end, in which Cleve and another pilot fight with almost empty tanks. The logic of this and other fights would have been difficult to understand without the introduction.

Other reviews

*******

The Hunters is the third book in the Literature and War Readalong 2016. The next book is the US novel Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain. Discussion starts on Friday 30 September, 2016. Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including the book blurbs can be found here.

Literature and War Readalong May 31 2016: The Hunters by James Salter

James Salter’s The Hunters is this month’s Literature and War Readalong title. It’s the first novel about the Korean war that we’re reading in the read along. I’ve been keen on reading James Salter for ages as he’s always mentioned as one of the greatest US writers. Published in 1956, The Hunters was Salter’s first novel. Until the publication of this novel, Salter was a career officer and pilot in the US Air Force. He served during the Korean war where he flew over 100 combat missions. This was certainly the reason why he chose to write about a fighter pilot in his first novel. The novel has been made into a movie starring Robert Mitchum and Robert Wagner. James Salter died last June in Sag Harbor, New York.

Here are the first sentences:

A winter night, black and frozen, was moving over Japan, over the choppy waters to the east, over the rugged floating islands, all the cities and towns, the small houses, the bitter streets.

Cleve stood at the window, looking out. Dusk had arrived, and he felt a numb lethargy. Full animation had not yet returned to him. It seemed that everybody had gone somewhere while he had been asleep. The room was empty.

He leaned forward slightly and allowed the pane to touch the tip of his nose. It was cold but benign. A circle of condensation formed quickly about the spot. He exhaled a few times through his mouth and made it larger. After a while he stepped back from the window. He hesitated, and then traced the letters C M C in the damp translucence.

And some details and the blurb for those who want to join:

The Hunters by James Salter, 233 pages, US 1957, War in Korea

Here’s the blurb:

Captain Cleve Connell arrives in Korea with a single goal: to become an ace, one of that elite fraternity of jet pilots who have downed five MIGs. But as his fellow airmen rack up kill after kill – sometimes under dubious circumstances – Cleve’s luck runs bad. Other pilots question his guts. Cleve comes to question himself. And then in one icy instant 40,000 feet above the Yalu River, his luck changes forever. Filled with courage and despair, eerie beauty and corrosive rivalry, James Salter’s luminous first novel is a landmark masterpiece in the literature of war.

*******

The discussion starts on Tuesday, 31 May 2016.

Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including all the book blurbs, can be found here.

Jean Echenoz: 1914 – 14 (2012) Literature and War Readalong March 2016

Jean Echenoz tells a very simple story in this short, compressed novel. Five men go to war; two of them return, three don’t. Two of them are brothers and in love with the same woman. The characters as such are not that interesting. What is interesting is what happens to them. Each stands for something that is particular to WWI. Charles is shot down when he joins a pilot to take pictures. The industrialization of war and the use of planes is new. Both elements were important for Echenoz and whole chapters are dedicated to them. One of the men is blinded by gas. That, too is a new and especially beastly feature of WWI. One man returns after having lost an arm. I don’t think any war saw as many mutilated men return. One of the men is executed because they mistake him for a deserter. The absurdity and farce of these decisions is made clear. One man dies during an attack. His body’s lost somewhere in the mud of no-man’s-land. All these are exemplary fates and could have turned the men into pure types, but thanks to Echenoz’s sense for detail, they are more than just types. Echenoz, as he said many times, isn’t interested in psychology. To convey a characters personality and emotions he sticks to pure “show don’t tell”. He describes the actions and the objects surrounding the characters. Both contribute to the description, one in a very realistic, the other in a more symbolic way. I think this was what fascinated me the most. Echenoz’s writing is so rigorous. There’s not one superfluous word. The vocabulary is refined, rich, and exact. He uses lists and enumerations, abstraction, numbers, irony. His writing is visual, even audiovisual because he tries to convey emotions through sounds.

1914 – 14 is one of those books that gets more interesting the more you read about it. My French paperback had about 40 pages of additional material, for which I was grateful, as an important element of Echenoz’s writing is intertexuality. I’ll give you one example. The story begins with Anthime on a hill. There’s a strong wind and suddenly he hears church bells ringing the tocsin that signals mobilisation. At the end of the scene, Anthime drives back to the village on his bicycle. He loses his book which has fallen from his bicycle and opened at the chapter “Aures habet, et non audiet”. What is interesting here is the fact that this whole scene is inspired, or rather taken from a scene in Victor Hugo’s Quatrevingt-treize – 93. It’s almost the same scene, only in Hugo’s novel, the character cannot hear the church bells, he only sees them moving. Echenoz who is interested in sound – the incredible noise is another new feature of this war – rewrote this scene, describing the sound of the bells. The book that Anthime carried with him is Hugo’s book. Allusions like these, which blend history and literature and the writing about history and literature are frequent and the closer you read, the more allusions you find.

When the book came out it was praised for its originality although Echenoz himself doesn’t seem to think it’s all that original. Here’s a quote from the book.

All this has been described a thousand times, so perhaps it’s not worthwhile to linger any longer over that sordid, stinking opera. And perhaps there’s not much point either in comparing the war to an opera, especially since no one cares about opera, even if war is operatically grandiose, exaggerated, excessive, full of longueurs, makes a great deal of noise and is often, in the end, rather boring.

I can see why critics found this original. His writing style is unique and he includes some chapters, like the one on animals, which is very different from what I’ve read in other WWI novels. The most original however is that he uses the techniques of the Nouveau Roman. One of these techniques is to explore nontraditional ways of telling a story. That’s why we find shifts in POV, intrusions of the author. Comments about the future etc. To some extent it is as much a book about writing as about war.

In an interview at the beginning of my edition, Echenoz names the three books that have influenced him the most when he wrote 14. Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front – Im Westen nichts Neues, Henry Barbusse’s Feu – Under Fire (Prix Goncourt 1916) and Gabriel Chevallier’s Peur – Fear, which we have read during an earlier Literature and War Readalong.

As short as this novel is, it’s very complex. Luckily, others have reviewed it too and much better than I.

I really liked Echenoz’s writing and would like to read more of him. Do you have suggestions?

Other reviews

*******

1914 was the second book in the Literature and War Readalong 2016. The next book is the a novel on the war in Korea, The Hunters by James Salter. Discussion starts on Tuesday 31 May, 2016. Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including the book blurbs can be found here.

Literature and War Readalong March 31 2016: 1914 by Jean Echenoz

This month’s readalong title is the slim novel 1914 – 14 by prize-winning French author Jean Echenoz. He has won the Prix Médicis for Cherokee and the Prix Goncourt for I’m off – Je m’en vais, both prestigious prizes, and a number of smaller prizes as well. He’s been on my radar for a long while and when I saw he wrote a novel set during WWI, I was immediately tempted. To be honest, the book has received mixed reviews. I’m very curious to find out on which side I’ll be.

Interestingly, the French title is 14 not 1914. One could probably discuss endlessly why they chose 1914 for the English translation and whether it’s right to change it like that. When I compared the beginning of the two books in French and English I noticed considerable differences. Those who read it in English, will have to tell me what they think of the translation.

Here are the first sentences:

Since the weather was so inviting and it was Saturday, a half day, which allowed him to leave work early, Anthime set out on his bicycle after lunch. His plan: to take advantage of the radiant August sun, enjoy some exercise in the fresh country air, and doubtless stretch out on the grass to read, for he strapped to his bicycle a book too bulky to fit in the wire basket. After coasting gently out of the city, he lazed easily along for about six flat miles until forced to stand up on his pedals while tackling a hill, sweating as he swayed from side to side. The hills of the Vendée in the Loire region of west-central France aren’t much, of course, and it was only a slight rise, but lofty enough to provide a rewarding view.

And some details and the blurb for those who want to join

1914 – 14 by Jean Echenoz, 120 pages France 2012, WWI

Here’s the blurb:

Jean Echenoz turns his attention to the deathtrap of World War I in 1914. Five Frenchmen go off to war, two of them leaving behind young women who long for their return. But the main character in this brilliant novel is the Great War itself. Echenoz, whose work has been compared to that of writers as diverse as Joseph Conrad and Laurence Sterne, leads us gently from a balmy summer day deep into the relentless – and, one hundred years later, still unthinkable – carnage of trench warfare.

*******

The discussion starts on Thursday, 31 March 2016.

Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including all the book blurbs, can be found here.

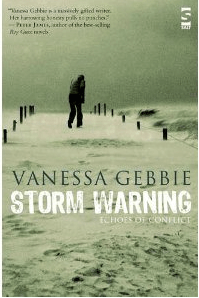

Vanessa Gebbie: Storm Warning – Echoes of Conflict (2010) Literature and War Readalong February 2016

Very often short story collections are just that – collections of stories that may or may not have a few themes in common. Most of the time, the themes are different, while the voice stays the same. Not so in Vanessa Gebbie’s stunning collection Storm Warning – Echoes of Conflict. The themes —war and conflict— are the same in every story, but the voices, points of view, the structure, the range of these stories is as diverse as can be. That’s why this collection is one of those rare books, in which the sum is greater than its parts. Each story on its own is a gem, but all the stories together, are like a chorus of voices lamenting, accusing, denouncing, and exploring conflict through the ages and the whole world. The result is as chilling as it is powerful and enlightening. I don’t think I’ve ever come across anything similar in book form and the only comparable movie, War Requiem, uses a similar technique only at the very end, during which we see horrific original footage taken from many different wars, covering decades, and dozens of countries.

We’ve often discussed the question of how to write about war in the Literature and War Readalong and I’ve said it before – if I put away a book and am left with a feeling of I-wish-I’d-been-there, then the book is a failure in terms of its anti-war message. I don’t think one should write about war and give readers a similar, pleasant frisson, they get when they read crime. I can assure you, you won’t have a reaction like this while reading Storm Warning. Without being too graphic, Vanessa Gebbie’s message is clear – there’s no beauty in war. There’s no end to war either. Even when a conflict is finished, it still rages on in the minds of those who suffered through it. Whether they were soldiers or civilians. War destroys bodies and souls. And—maybe one of the most important messages— war is universal. Including stories set in times as remote as the 16th century, choosing locations as diverse as South Africa, the UK, and Japan, conflicts like WWI, WWII, the Falklands war, Iraq, Vietnam, and many more, illustrates this message powerfully. Choosing from so many different conflicts also avoids falling into the trap of rating. I always find it appalling when people rate conflicts, saying this one was worse than that one. Maybe the methods are more savage in some conflicts, but they are all equally horrific.

What is really amazing in this collection is that so many of the stories get deeper meaning because they are juxtaposed with other stories. For example, there’s the story The Ale Heretics set in the 16th Century, in which a condemned heretic, awaits being burned. Burning people alive was such a savage and abominable thing to do, but just when we start to think “Thank God, that’s long gone” – we read a story about necklacing, a form of torture and execution, practiced in contemporary South Africa (possibly in other regions too), in which the victims are also burned alive. And, here too, it’s said to be in the name of the law. If I had only read the first story, it wouldn’t have been as powerful as in combination with the second.

Vanessa Gebbie’s writing is very precise, raw, expressive. As I said before, each story has a distinct voice. There are men and women talking to a dead relative, others seem to try to explain what happened to them, others accuse, many denounce. Yet, as precise as the writing is, often there’s an element of mystery as to what conflict we are reading about. While it’s mostly clear, what conflict is described, they are rarely named. Interestingly, this underlines the similarity and universality, but it also makes differences clear. When a girl talks to her dead sister Golda, mentions the Kristallnacht, we know, it’s a Holocaust story. When gas gangrene is mentioned, we know it is about WWI.

Many of you might wonder, whether the stories are not too graphic, whether the book is depressing. There’s a balance between very dark and dark stories. There’s a touch of humour here and there, even if it’s gallows’ humour, and there’s the one or the other story that’s almost uplifting like my own personal favourite Large Capacity, Severe Abuse. In this story, a Vietnam veteran lives in the basement of an apartment house for retired army officers. He’s in charge of washing their laundry which gives him an opportunity for revenge. This story illustrates also the invisibility of many veterans. They are decorated, they return, they suffer, but society doesn’t care. Some of the veterans in this collection, end up homeless. Too sum this up— the collection is not easy to read, as it’s quite explicit in showing that war mutilates bodies and souls.

Another favourite story was The Return of the Baker, Edwin Tregear. It’s a story that does not only illustrate the difficulties of the homecoming, but the absurdity of things that happened during the war. In this case WWI and its practice of firing soldiers for so-called cowardice.

Some of the stories describe a narrow escape like in The Salt Box, in which a dissident poet finds an unexpected ruse to destroy his poems when his house is searched.

The narrators and characters in these stories are of different gender and age. Stories that have child narrators are often particularly harrowing. There’s the one called The Wig Maker, in which a child witnesses the execution of the mother, and another one, The Strong Mind of Musa M’bele, in which the kid knows his father will be necklaced. Another kid, in Cello Strings and Screeching Metal, witnesses someone being shot while climbing the Berlin Wall.

Quite a few of the stories are more like snapshots; they are very brief, only a page or two, but there are some longer ones as well.

I must say, I’m impressed. The range of these stories is amazing. Getting voice right and distinct, is a difficult thing to do and to get it as right and as distinct in so many stories is absolutely stunning. This is certainly one of the most amazing and thought-provoking anti-war books I’ve ever read.

Should you be interested, one of the stories – The Wig Maker – is available online. Just a warning – it’s possibly the most explicit of the collection.

Vanessa Gebbie is joining our discussion, so, please, don’t hesitate to ask questions.

Other reviews

*******

Storm Warning is the first book in the Literature and War Readalong 2016. The next book is the French WWI novel 1914 – 14 by Jean Echenoz. Discussion starts on Thursday 31 March, 2016. Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2016, including the book blurbs can be found here.