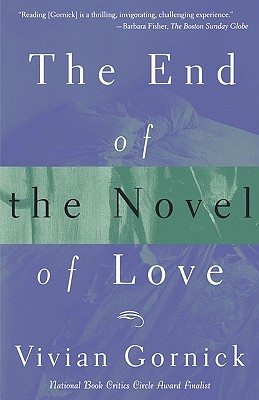

In these essays Vivian Gornick examines a century of novels in which authors have portrayed women who challenge the desire to be swept away by passion. She concludes that love as a metaphor for the making of literature is no longer apt for today’s writers, such has the nature of love and romance and marriage changed. Taking the works of authors such as Willa Cather, Jean Rhys, Christina Stead, Grace Paley and Hannah Arendt, Gornick sets out to show how novels have increasingly questioned the inevitability of love and marriage as the path to self-knowledge and fulfilment.

Vivian Gornick is an essayist and memoirist. Her collection The End of the Novel of Love contains a wide range of essays on different authors and topics. The title is the title of one of the essays. Almost all the essays circle to some extent around the topic of love. Some of the essays are more biographical, others focus more on a theme and compare and analyse different authors and works.

There are biographical essays on Kate Chopin, Jean Rhys, Willa Cather, Christina Stead and Grace Paley. I liked the one on Willa Cather and Grace Paley best, as Gornick is less judgmental in them than in some of the others. In the essay on Paley she says that despite the fact that her range isn’t all that wide, that Paley often writes about the same things again and again, her stories are still excellent because in her stories the voice is the story. What is unique in her stories is that people don’t fall in love with each other but with the desire to be alive.

There have been three story collections in thirty-five years. They have made Paley famous. All over the world, in languages you never heard of, she is read as a master storyteller in the great tradition: people love life more because of her writing.

The book contains two essays on people who are not fiction writers: Hannah Arendt and Clover Adams. While I’m familiar with Arendt and her work, I didn’t know the tragic story of Clover Adams, the wife of Henry Adams, who took her own life in 1885. The suicide struck Henry Adams particularly hard as he thought of Clover and himself as two parts of a whole, while, very clearly, Clover had an inner life of her own and didn’t share most of her distress. Clover was, according to Gornick, extremely intelligent and witty, which fascinated Adams. He fell in love with her mind right away, but didn’t show much kindness when he wrote about her as being anything but handsome. And even his praise of her intelligence doesn’t really read as a praise because he feels obliged to add – implicitly and explicitly – that she’s witty and intelligent “for a woman”.

The most interesting essays in the collection are those on themes, in which Gornick analyses and compares several works.

In Diana of the Crossways Gornick compares George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, George Meredith’s Diana of the Crossways and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. Gornick tells us that while the three books written by women are brilliant, they aren’t a success, unlike Diana of the Crossways, which is a stunning novel, because it goes one step further.

Each of these three novels was written by a brilliant woman with the taste of iron in her mouth. Each of them gives us a sobering portrait of what it feels like to be a creature trapped, caught stopped in place. Yet no one of these novels penetrates any deeper than the others into the character’s desire to be free: all that is achieved here is the look and feel of resistance. (…)

George Meredith, in his late fifties, had the experience and the distance. Meredith knew better than Woolf, Eliot, and Wharton what a woman and a man equally matched in brains, will, and hungriness of spirit might actually say and do, both to themselves and to one another. (…)

Diana Warwick is one of the first women in an English novel both beautiful and intellectually gifted who needn’t be dismissed as vain, shrewd, and ambitious before we can get on with it.

Ruthless Intimacies analyses the relationship between mother and son in D.H.Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, and the relationship between mothers and daughters in Radclyffe Hall’s The Unlit Lamp, May Sinclair’s Mary Oliver, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and Edna O’Brien’s short story A Rose in the Heart of New York. The relationships in these novels are symbiotic and swallow up the daughters completely. They struggle their whole lives to free themselves. I can relate to that all too well and would really love to read The Unlit Lamp and Edna O’Brien’s short story. Both sound pertinent and excellent.

Tenderhearted Men focusses on author’s who write in the vein of Hemingway about men and women. Raymond Carver, Richard Ford and André Dubus. Gornick dismisses them as too sentimental. They cling to a dated idea of men being saved by women, without trying to understand them.

The End of the Novel of Love is interesting. It states the obvious but the obvious was still worth stating. Most of the tragic (love) stories of the past like Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina, but also books like The House of Mirth are unthinkable in our day and age. Marriage and society have changed so much. Adultery doesn’t have the social consequences it had. I thought this part of the essay interesting, but I didn’t like that she chose to illustrate her concept in picking apart Jane Smiley’s novella The Age of Grief and calling it not only unmoving, but a failure. Harsh words. Maybe it’s true. I haven’t read it but I don’t like this type of unkind criticism.

Gornick’s writing is very accessible, a lot of her insights are fascinating and made me think, but, as I mentioned before, she’s very judgmental, which made me cringe occasionally. It made Gornick come across as very unkind. See for example this passage taken from the essay on Kate Chopin.

One of her biographers makes the point that Chopin never revised, Chopin herself, announced, in interview after interview throughout her professional life, that the writing either came all at once, or not at all. I think it the single most important piece of writing we have about her. She seems to have considered this startling practice a proof of giftedness, rather than of the amateurishness that it really was.

Although I didn’t care for some of her harsh judgments, I thought many of her observations were pertinent and fascinating and I’d certainly read another of her books. I’m interested in her memoir Fierce Attachments and her book on creative non-fiction The Situation and the Story: the Art of Personal Narrative.

If you’re interested here’s the first chapter on Diana of the Crossways.