Ballard is an author I’ve always wanted to read, but I was never sure which novel to pick first, so I postponed reading him again and again. Why I finally picked The Drowned World is an interesting story because it mirrors the content of the book in an uncanny way.

I keep on dreaming about the city I’m living in. In my dreams it doesn’t look like the actual city but is completely overgrown, drowning in vegetation, all the streets look like rivers of grass. It’s not hot in this city and it’s not necessarily a post-apocalyptic setting, but it’s a completely altered landscape. Curious to see whether anyone ever wrote something like this, I googled a few key words, which eventually led me to Ballard’s The Drowned World. What an amazing experience to find an echo of my own dreams and imagination in this book. Furthermore I have always been very fond of surrealist paintings and the idea of archetypes makes sense to me; both are important elements in this novel.

The Drowned World is set in a post-apocalyptic world, or, to be more precise, in a submerged, overgrown, tropical lagoon that once used to be the city of London. Solar radiation melted the ice-caps; the land was flooded. The heat and the floods have changed the climate completely.

Dr Robert Kerans, a team of researchers and an army unit map the flora and fauna of the different lagoons. While the team wants to move north, Kerans and a few others want to remain south. They have begun to dream strange dreams, which are a sign of their devolution. It seems as if they were regressing; the changing landscape has affected their psychology.

As Bodkin, one character, says:

“Well, one could simply say that in response to the rises in temperature, humidity and radiation levels the flora and fauna of this planet are beginning to assume once again the forms they displayed the last time such conditions were present – roughly speaking the Triassic period.”

Because the landscape once used to look like it does now, the subconscious of the people reacts:

“But I’m really thinking of something else. Is it only the external landscape which is altering? How often recently most of us have had the feeling of déjà vu?, of having seen all this before, in fact of remembering these swamps and lagoons all too well.”

The premise is that everything the species has ever experienced is stored in the subconscious of each one of us and with the devolution, the memories are triggered:

“The brief span of an individual life is misleading. Each one of us is as old as the entire biological kingdom, and our bloodstreams are tributaries of the great sea of its total memory.”

I thought this was highly fascinating and it does make sense. Maybe not as literally as Ballard states it, but it’s sure that landscape influences us, it even influences our deep psychology, and it’s entirely possible that the memories of the species are stored in our subconscious as well.

The novel is not very action-driven but there is conflict. At first the army wants everyone to leave and move up north, but they finally give in and depart. Kerans, Bodkin and Beatrice Dahl – Kerans enigmatic lover – stay behind. They know they will not be able to survive for long but before they can decide on their future Strangman and a group of pirate-like characters appear. They are looters. They travel from lagoon to lagoon and rob all the submerged buildings of their riches. What nobody knows at first is that they dry up the lagoons and towards the end of the novel, we see the silt- and algae-covered London emerge from the waters. Another uncanny moment.

The end is predictable, but that doesn’t make it any less powerful. It reminded me a lot of Joseph Conrad’s Almayer’s Folly.

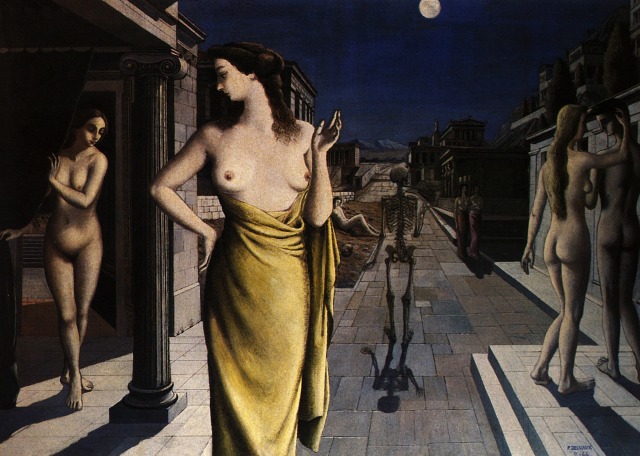

My edition of the novel contains an interview with Ballard and a short essay by him. In these two texts he underlines that surrealism, dreams and the fact that he grew up in Shanghai were important in the writing of this book. Max Ernst and Paul Delvaux are mentioned in the novel and have influenced Ballard’s imagery. As a child he witnessed how Shanghai was flooded every summer and that as well has contributed to create the images in the novel.

Max Ernst

Paul Delvaux

The Drowned World is not an easy book because it’s heavy on descriptions. As a lot of what he describes felt familiar from my dreams and my travels to Asia, it was easy for me to see what he painted with words, but I suppose it could be a challenge if you prefer action driven books. If you have never experienced the humid heat of the tropics it’s equally hard to imagine how that climate could affect you. That’s why I compared it to Conrad. The way Westerners are affected by the tropics is quite explicit in Conrad’s work, while it is much more implicit in Ballard’s book. Comparing the two is interesting.

I know that I wasn’t able to do this book justice. I think that is because I liked it too much. That may sound weird but that’s how it is. The Drowned World is one of the most fascinating books I’ve ever read. I loved the premise and the imagery; it was so powerful, reading it felt like lucid dreaming. It’s making my best of this year list, and maybe even my all-time favourite list.