I’m so pleased to have a few guest posts for you from one of the blogs I admire the most. literalab is my go-to blog for Central and Eastern European fiction. Michael is an American expat living in Prague. He is a journalist and writer and has written for different European and American magazines. His posts have always something completely new to offer. Either because the writers are new to me, or because the angle from which he writes about them is unusual. For German Literature Month he has written a few guest post on Prague German writers. We kick off today with an introduction, tomorrow I’ll feature one of his reviews. You will see, there are far more Prague German writers than Kafka to be discovered or re-discovered. The posts wich will follow are part of a series. I’ll feature a few, the following will be posted on literalab in the upcoming weeks.

As the number of early 20th century German-language writers such as Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig get “rediscovered” and belatedly translated into English there is the impression that the deep literary mines of the era might have dried up and all that’s left are the correspondence and diaries of those same writers, or perhaps a new translation of Kafka’s second-grade homework or some of his miscellany that will inevitably come out of the recently litigated manuscript stash in Tel-Aviv.

That impression is, of course, wrong, and one of the sources of the many German-language writers still left to be read, re-published and even translated for the first time happens to be the same source as those contentious manuscripts and the posthumously famous “prophet of the 20th century” who wrote them in the first place – Prague.

Recently, Prague German writers have finally been getting rediscovered to a certain degree, though generally without getting profiled in the New Yorker like Joseph Roth or shredded in the London Review of Books like poor Stefan Zweig (the exception is Ruth Franklin’s New Yorker profile of H.G. Adler, unavailable online.) I have written about a recent exhibition on Prague’s Forgotten German Writers at Readux and a number of the writers I’ll list have been republished or published for the first time in English only this year.

This will be a totally unsystematic list, consisting of writers I love and have read and reread, writers I haven’t read in a long time and some I haven’t gotten around to reading yet at all. I wanted to put them all there to show the variety of Prague’s now vanished literary scene.

These writers suffered from some very stark and evident wrongs – they grew up in an atmosphere of nationalist intolerance, and with many of them Jewish, experienced Czech nationalism at first as harshly, if not more harshly, than its German counterpart. Later, they experienced more severe repression, exile, and privation.

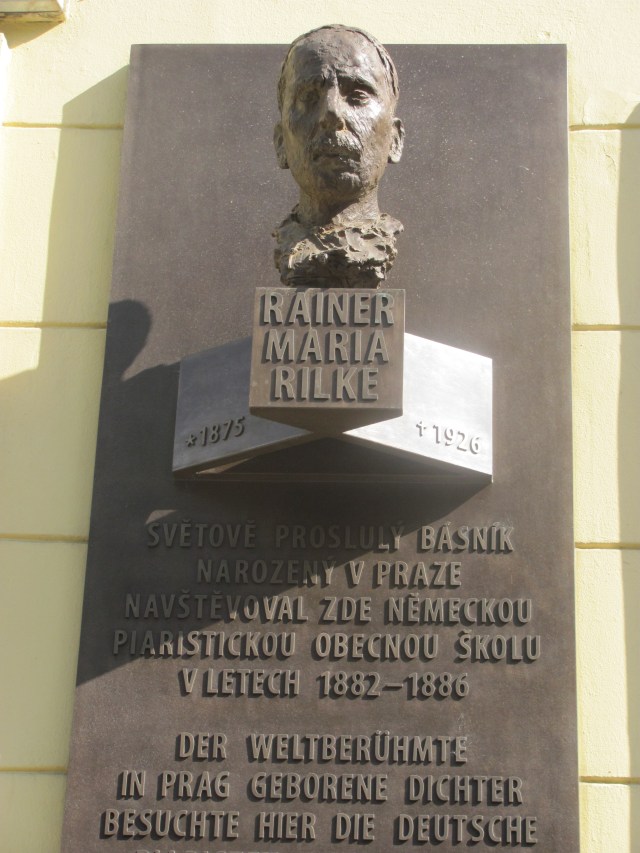

One ironic result of Nazism’s defeat, in combination with the Holocaust, was that their language was erased from their homeland. This meant that Prague German writers became almost unknown in their homeland, and even today putting up a public bust to a world-renowned figure like Rilke took until 2011, seemingly after all the busts of Czech choral directors and dental school founders had found there eternal homes.

Yet perhaps the darkest and most obscuring shadow for this group of writers has been that of their canonized compatriot Kafka. Their work is compared to his (even by people who haven’t read theirs) in a way that is patently unfair and which would kill off any number of other national literatures of the period if their work was put to a similarly unfair test. Kafka’s labyrinths are supposed to be a stand-in for the streets of Prague, so then why read about those actual streets? Well, I can think of any number of reasons, one of which is that Kafka’s labyrinths aren’t a stand-in for the streets of Prague.

Prague offered a fantastic starting point for its writers to go in a multitude of directions, Kafka included, but where he uses a sparse prose style to delve into layers of symbolic meaning, Leo Perutz, for example, makes use of the city’s rich history and myth, whereas writers like H.G. Adler and Hermann Grab ventured into entirely different realms of modernist writing, often being compared to Joyce and Proust respectively.

Thanks a lot, Michael, for this great contribution. Tomorrow I will post the sequel, the first name on the list of Prague German writers. The list will be continued in the upcoming weeks and will either be featured on this blog or on literalab.