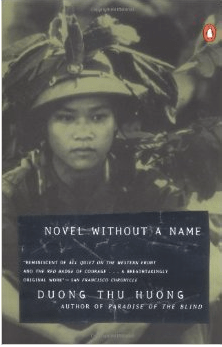

Two years ago we read Bao Ninh’s moving novel on the war in Vietnam The Sorrow of War. Quite a few of those who participated and others who read our posts stated that they would be interested in reading novels by Vietnamese authors. That’s why I chose to include Novel Without a Name – Tiêu thuyêt vô dê, another famous novel on the war in Vietnam. It was written by one of Vietnam’s most prominent authors: Duong Thu Huong. She is well-respected outside of her native country. If you read French you’ll find translations of many of her books. Duong Thu Huong is not only a great writer but a courageous one. Many of her novels have been forbidden in Vietnam and she was imprisoned for her political views.

This link will lead you to the website of Swiss publisher Unionsverlag. Unionsverlag is a pioner when it comes to world literature. On their website you’ll find newspaper articles and interviews on and with Duong Thu Houng – in English.

Here are the first sentences (which I had to translated from my German copy)

I heard the wind howl all through the night, out there, over the ravine of the lost souls.

It sounded like a constant moan, like sobbing, then again like cheeky whistling, like the neighing of a mare during copulation. The roof of the pile dwelling trembled, the bamboo poles burst and whistled every time like reed pipes. They played the mournful melody of a country burial. Our nightlight flickered as if it was going to die down. I stretched my neck from under the quilt, blew out the light, and hoped that the shadow of the night would cover up all the senses . . .

And some details and the blurb for those who want to join

Novel Without a Name – Tiêu thuyêt vô dê by Duong Thu Huong (Vietnam 1995), War in Vietnam, Novel, 304 pages.

Vietnamese novelist Huong, who has been imprisoned for her political beliefs, presents the story of a disillusioned soldier in a book that was banned in her native country.

A piercing, unforgettable tale of the horror and spiritual weariness of war, Novel Without a Name will shatter every preconception Americans have about what happened in the jungles of Vietnam. With Duong Thu Huong, whose Paradise of the Blind was published to high critical acclaim in 1993, Vietnam has found a voice both lyrical and stark, powerful enough to capture the conflict that left millions dead and spiritually destroyed her generation. Banned in the author’s native country for its scathing dissection of the day-to-day realities of life for the Vietnamese during the final years of the “Vietnam War, ” Novel Without a Name invites comparison with All Quiet on the Western Front and other classic works of war fiction. The war is seen through the eyes of Quan, a North Vietnamese bo doi (soldier of the people) who joined the army at eighteen, full of idealism and love for the Communist party and its cause of national liberation. But ten years later, after leading his platoon through almost a decade of unimaginable horror and deprivation, Quan is disillusioned by his odyssey of loss and struggle. Furloughed back to his village in search of a fellow soldier, Quan undertakes a harrowing, solitary journey through the tortuous jungles of central Vietnam and his own unspeakable memories.

*******

The discussion starts on Friday, 29 May 2015.

Further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2015, including all the book blurbs, can be found here.