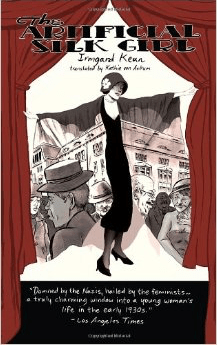

When you are part of a writers’ group, it’s only natural to discuss books. And so, a while ago, I mentioned German Literature Month on my writer’s forum and found out that one of the members. John Lugo-Trebble, had studied German literature and did research on Irmgard Keun (and other authors). While discussing, he said that he found she deserved to be more widely known, especially her masterpiece The Artificial Silk Girl – Das kunstseidene Mädchen. I certainly agree with him, and so I asked him whether he felt like writing a guest post for German Literature Month. I’m very glad he said yes. John Lugo-Trebble is an American writer, living in the UK. Some of his short fiction is forthcoming on Jonathan the literary journal of Sibling Rivalry Press.

My Case for “The Artificial Silk Girl” – by: John Lugo-Trebble

Christopher Isherwood’s “Berlin Stories” was the inspiration for “Cabaret” which for an English speaking audience is often the image conjured up of Weimar Berlin. His Berlin is a decadent melting pot on the brink of implosion through the eyes of fun seeking expats. I don’t think you can argue that his observations are not important but for me, reading is like travelling and when I travel I always like to experience what locals would. This is why for me, one of the most important German texts capturing the era that should be read by English speakers is “Das kunstseidene Mädchen” (“The Artificial Silk Girl”) by Irmgard Keun.

Irmgard Keun gives us not just a German insight but a female German insight to Weimar through the eyes of her protagonist Doris. Working in a theatre in Köln, young Doris craves the spotlight, like the women in the glossy magazines that are like her Bible. She wants glamour, she wants wealth. She doesn’t want to be like her parents, on the breadline. She especially fears becoming her mother and having to support a man, in a loveless marriage. Doris becomes enamoured with a fur coat at the theatre and decides to steal it. In her fur coat, she can dream of the life she so covets. She can pretend to be that wealthy young girl who deserves the finery in life. She can epitomise glamour when wrapped in the soft fur. Now a fugitive because of this coat, she runs to Berlin wherein her vain attempt in pursuing glamour she weaves through the city’s underworld of prostitutes, pimps, communists and even becoming a mistress herself. Her dreams quickly spiral out of control as she chases money, stability and ultimately love amidst the backdrop of Berlin’s economic and political turmoil; putting us in mind of one of Grosz’s paintings come alive.

On the one hand, Doris is a mirror of the limitations of the New Woman, a woman who was to be liberated from the shackles of Imperial Germany by the promise of the Social Democratic Weimar Constitution. The reality is the limitations of that liberation that came with the economic upheaval left by the Treaty of Versailles. There is though something in Doris’ tale that resonates still today and that is the pursuit of glamour, a desire for celebrity.

I was reminded only recently of “The Artificial Silk Girl” when I was watching “The Bling Ring.” For those of you who haven’t seen it, the film is loosely based on a crime spree in Los Angeles perpetrated by a group of celebrity admiring, glamour seeking teenagers who literally break into the houses of their style icons to steal their possessions. They are driven by this desire and need to be famous, to lead an untouchable existence of celebrity. I couldn’t help but think of Doris. The difference though is that Doris has a moral centre which comes forward as she sits on a bench at Bahnhof Zoo, no longer the girl start struck in pursuit of wealth, she is a woman aware of the world around her, her own limitations, and indeed her own desires. Will she head out of Berlin or stay? We don’t know, but what we do know is that the fur coat is long gone now.

Irmgard Keun is one of the few German women writers of her day who have been translated into English and I truly believe one of the finest writers of the Twentieth Century, full stop. She presents us with a protagonist who has the naiveté of youth and the observational skills of a woman of her day. You will fall in love with her vulnerability, laugh at her silliness and want to shake her till she grows up but also respect her path because she tries, even when there is no hope presenting itself. With Keun, there is a voice beyond Alfred Döblin and Hans Fallada’s portrayals of women which leave much open to debate. There is more than Sally Bowles.

*****

Thanks so much, John, for this interesting post. I hope those who haven’t done so yet, will soon pick up The Artificial Silk Girl, or one of Keun’s other great novels.