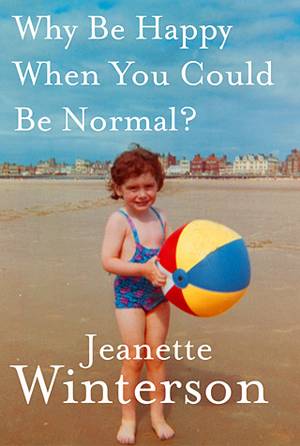

In 1985 Jeanette Winterson’s first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, was published. It was Jeanette’s version of the story of a terraced house in Accrington, an adopted child, and the thwarted giantess Mrs Winterson. It was a cover story, a painful past written over and repainted. It was a story of survival.

This book is that story’s the silent twin. It is full of hurt and humour and a fierce love of life. It is about the pursuit of happiness, about lessons in love, the search for a mother and a journey into madness and out again. It is generous, honest and true.

Jeanette Winterson’s first novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit is largely inspired by her childhood. Her memoir Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? tells the other side of the story. That what was left out. It took me a long time to read this memoir. I started it four times, not because it’s not good, but because reading it was painful. The first part, until Jeanette leaves home at 16 and her mother asks her the question that has become the title of the book, is painful and disturbing for many reasons. The wit and the humor she uses to describe her awful childhood made me shudder. Shudder because I didn’t get it. I didn’t understand how you could live through so much pain and not go crazy, to write a book at 21 and become famous and leave it all behind. I was glad she proved to be so resilient, but it made me uneasy. I kept on thinking: When is it going to happen? When will she break down? Is that still in the future? I don’t think that you can survive a childhood like Winterson’s and not break down eventually. It’s just a matter of time.The second part of the book deals with what came much later. Jeanette Winterson’s descent into madness (her terms), her breakdown and attempted suicide in 2008. Reading that felt like entering a freshly aired room. I know this may sound weird, but the beginning made me choke. I couldn’t believe that she’d left it all behind and only when I read about the descent into madness, did I finally feel glad for her. Now she can move on.

Jeanette Winterson was adopted by the Wintersons when she was 6 months old. She was never told who her real parents were and her mother always said that the devil led them to the wrong crib, meaning she would have liked another child, a nicer child. This is such a typical statement from a woman like Mrs Winterson who is a depressed zealot and always utters half-truths in bible-inspired metaphor. Jeanette Winterson says that all of her books start with individual meaningful sentences and we see where that comes from. Her mother often only says one dark ominous sentence over and over again. Sometimes without any apparent connection to what just happens or what was just said. “Ask not for whom the bell tolls . . .”, “It’s a fault to heaven, a fault against the dead and a fault to nature . . . ” Uttered without any context or referring to very mundane things like the gas oven blowing up, these sentences are either creepy or hilarious.

Winterson grew up in the North of England, near Manchester and she loves this part of the country, lovingly tells us about its history, which is quite interesting. The Wintersons are not only religious fanatics but working class and her mother is so suspicious of books that she confiscates and burns all of those Jeanette has been hiding.

Punishment is frequent and comes in different forms. Either Jeanette is beaten or left outside all night and day, on the door step, even in winter.

When she falls in love with a girl, and Mrs W finds out, they perform an exorcism. Jeannette finally leaves at 16. She only returns once, when she’s studying in Oxford and things go very wrong. That’s the last time she sees her mother.

As you may have guessed, this isn’t an easy book to write about. I marked so many passages and sentences that hardly any page is left white. Jeanette Winterson has a way with words that is amazing. Although I don’t always agree, I find the sentences, many of which are used in her novels, arresting.

In her novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, Jeanette Winterson paints her mother like a giantess and in her memoir she says she was too large for her circumstances. I was puzzled that there was no explanation whatsoever why Mrs W was the way she was. Mean, fanatic, abusive, depressed and just plain crazy. She had her dreams and her wishes, but smothered them. She lived as if she was wearing a very tight corset. The Wintersons were Pentecostals and the religion was like a mental corset.

If you like memoir, then you should read this. It’s disturbing, but it’s so amazingly well written and the first part has hilarious moments. Mrs Winterson is crazy, but she really is larger than life. She reminded me of some of Picasso’s paintings of grotesquely deformed women. We read about her with horror, but at the same time we almost wishes we had been there. I even felt compassion, there were small details that could almost make her endearing. At the end of the book, when Jeanette Winterson has found her birth mother and looks back on her childhood, she says she’s glad Mrs Winterson was her mother. Although she was crazy and abusive, she made her who she is, maybe without such an adoptive mother, there wouldn’t be a writer like Jeanette Winterson. I can understand that thinking very well.