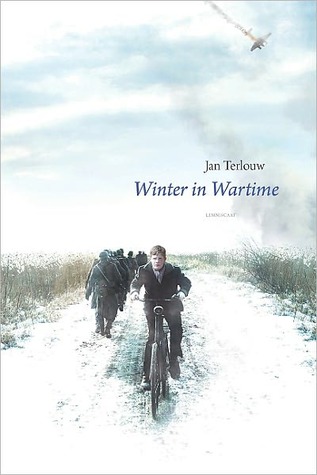

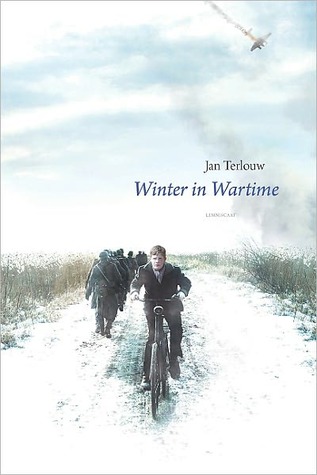

Dutch author Jan Terlouw’s award-winning novel Winter in Wartime (Oorlogswinter), which has been made into a movie, is a book for YA. It tells the story of 15-year old Michiel and is set during the hunger winter, in the Netherlands in 1944.

Michiel lives in a Dutch village with his parents, older sister and younger brother. His father is the mayor of the village. Like the rest of the Netherlands, their village is occupied by the Germans. It’s obvious for everyone that the war will come to an end soon and that the Germans are losing it. However, instead of giving up, they intensify their hostile activities; they search houses, arrest, torture and shoot people.

The village is divided, some are collaborating, some are suspected to collaborate, while others are in the resistance. Michiel’s parents are anti-German; they are good people who try to help those who have less, as much as possible. Every night they open their doors to distant relatives, people on the run, displaced persons, provide shelter and food for one night. Uncle Ben who is in the resistance is one of the regulars.

Michiel has an outsider position. He isn’t really a child anymore but doesn’t seem old enough for resistance work. When Dirk, an older boy who has joined the resistnace, asks him to deliver a letter, should he not return from a mission, Michiel feels honoured.

That same day his father and a group of other people is arrested because someone has killed a German soldier. Some of the men who are arrested will be hanged. When Dirk doesn’t return and Michiel fails to hand over the letter, he opens it and discovers that Dirk has been hiding a wounded British pilot. What should he do now? Who will help him? Is there anyone he can trust? That’s what you will discover if you decide to read Winter in Wartime.

Towards the end of the book (p. 121) Michiel remembers something his father said

Michiel often thought of something his father once said: “In every war dreadful things happen. Don’t think that it is only the Germans who are guilty. The Dutch, the British, the French, every nation has murdered without mercy and perpetrated unbelievable tortures in times of war. That is why, Michiel, you shouldn’t allow yourself to be misled by the romance of war, the romance of heroic deeds, sacrifice, tension and adventure. War means wounds, sadness, torture, prison, hunger, hardship, and injustice. There is nothing romantic about it.”

This short paragraph is central and summarises the theme of the book. The novel looks exactly into this and tests it. While the story confirms that war is horrible, it still shows that heroism is possible. There will always be courageous and kind people in every war, people who will try to stay good and do good.

This is a book for young people and I was very interested to see how WWII would be handled. In all the resistance books and movies torture plays an important role. How would that be handled for children. I’d say Terlouw did a great job. He was explicit but not gruesome. Not for one second we think it may not have been as bad but still he isn’t too explicit.

Books for children and YA always have a message. A lot of that message is captured in the quote above but there is another central theme, which is illustrated too – not every German was bad. No people is bad as a whole.

I think Terlouw’s book is well done, it captures he Netherlands during the winter of 44 very well. The hunger, the masses of fleeing people, the occupation, the suspicions, all this is well drawn. The tone isn’t depressing as the end of the war is in sight. Horrible things happen still but there is a lot of hope.

I saw the movie a few years ago that’s why I possibly didn’t like the novel as much as I would have if I hadn’t known the story already. It isn’t one of my favourite readalong titles but it’s still well worth reading and, as a children’s book, I’d say, it’s excellent. Don’t miss it if you’re interested in WWII, occupied Holland, the Dutch resistance, and are looking for all of these topics done in a way that is appropriate for younger readers.

Other reviews

Anna (Diary of an Eccentric)

Danielle (A Work in Progress)

Iris (Iris on Books)

Judith (Reader in the Wilderness)

Movie review

Kevin (The War Movie Buff)

*******

Winter in Wartime was the sixth book in the Literature and War Readalong 2013. The next is the novel is Children of the New World aka Les enfants du nouevau monde on the war in Algeria by Algerian writer Assia Djebar. Discussion starts on Monday 29 July, 2013. Further information on the Literature and War Readalong, including the book blurbs can be found here.